Last week, we met a muse of Munch’s, and thought about muse-ry in more general terms. We said that while it is the artist that tells us – or shows us – a story, it is the muse that sparks it. And though we can read back through history and slot figures in the role of muse for Munch, his artwork shows us that inspiration and his emotional response are bound together. We said that it was impossible for him to let an outside force inspire his artwork without inserting himself into the mix, the characterization of the artwork equating to the magnitude of his emotional being, his ego. But we’re here to talk about Picasso today – and as we well know, he unapologetically had a muse for every major era of his work. Following our line of inquiry from last week’s special on Munch, though, it is interesting when Picasso too thinks about the muse, when he represents the concept rather than draws on her voice.

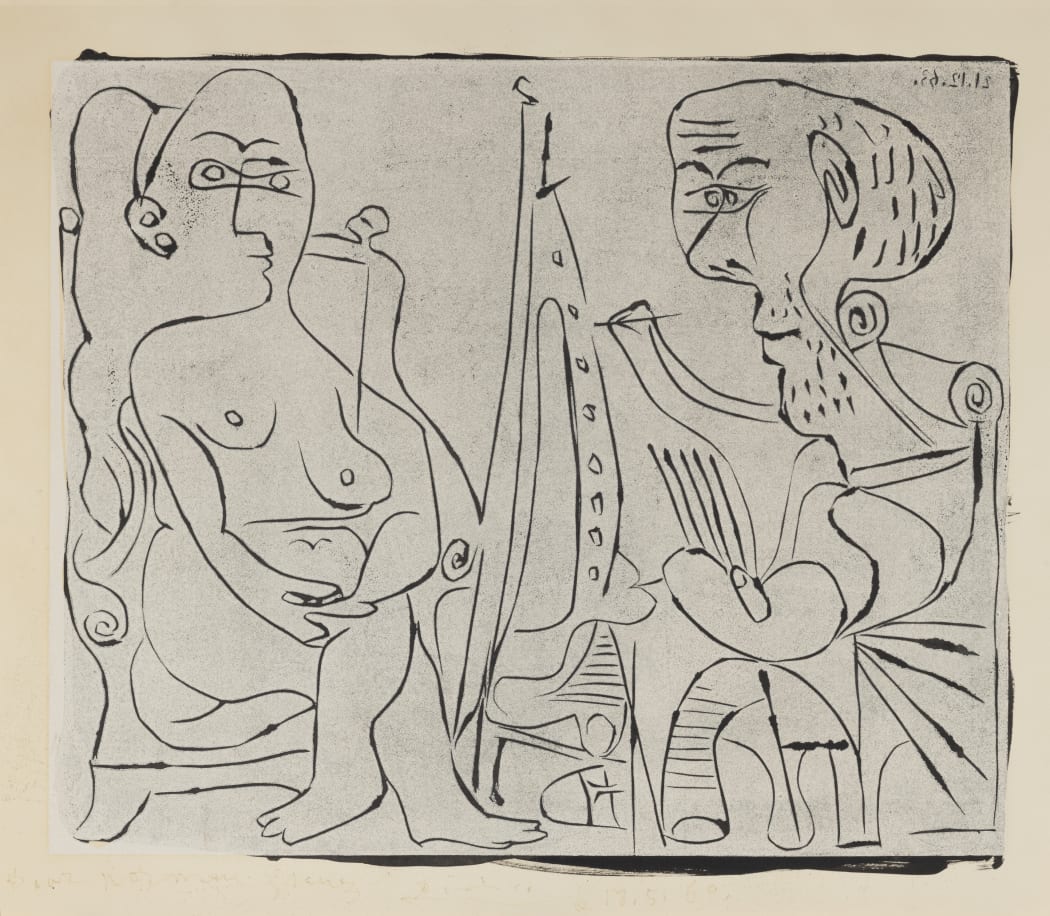

To illustrate this, we turn to Peintre et modèle au fauteuil (Ba1347), a late linocut rince in Picasso’s oeuvre and one of the furthest prints down the line of his career currently living in the gallery. The image was created in 1963, when Picasso was eighty-two years old. There’s no point in crafting any pretty way to say it: he’d grown old, and he was aware that he was living in an old man’s body. He was not interested in representing himself any differently – interesting, given that he had constantly sought alternative ways to do just this when he was a younger man (see below: a work from the Suite Vollard, Sculpteur travaillant sur le motif avec Marie-Theresa posant (B168), part of the sculptor’s studio series). There are a few motifs that run through Picasso’s later-year prints, and one is the inflation, the emphasized baldness, of his self-represented head; as though he imagined that his thinking organ had ballooned from his years the same way his skin sagged had in them. The inflated head is, of course, a symbol for wisdom in age, knowledge you cannot rid yourself of (as much as you might like to); but it’s also rather un-symbolic, rather a plain way for Picasso to say to us: I know I am old. In Ba1347, the distinction is brought even further into focus as we juxtapose the artist with his comparatively youthful model.

Between the end of October and December 1963, Picasso ruminated on the subject of artist and model, creating a group of at least twenty prints studying it. In all, the canvas is shown at a right or slightly acute angle to the viewer – making it clear that we are not meant to sneak glances at the unfinished subject, or make abject interpretations about the self-referentiality of the work. Rather, the focus of this series is on the cast of characters in the studio, which (as our artwork above shows) always included the painter at his canvas and his model before it. Often other spectators appeared – both human and mythically made-up – as though the studio were a stage, Picasso’s stage.* Even after a career over six decades long, Picasso refused to assert his studio as a locus of serious contemplation, of assumedly important artmaking. He still viewed what he was doing – indeed, asked us to view what he was doing – as sensual, comedic, satiric, confrontational, but always as a comedy of errors, always as play. In this way, his representation of muse is surprisingly subtle – it doesn’t really seem to be about his beautiful model, so restrictively. Rather, it’s the interaction between the two characters, the space in which they commingle. Muse is the humanity (and, as the opposite of anything is often equally as true, the inhumanity) of making art.

1963 is approximately the beginning of Picasso’s final epoch. To be frank, this period is often considered to lack the sex appeal of his others, and therefore is, sadly, somewhat neglected. And yet, as we’ve witnessed today, it is within this subset of impressions that we see some of Picasso’s most psychologically complex, some of his most character-revealing works. In the future, we may return to some of those undersung works. Until then, I wish you a safe and restorative weekend.