People often ask me, why Munch and Picasso? What is the through line that is the basis of your attraction? Though I could give you a list, one encompassing point would always stand out: their prints are records, visual autobiographies of their lives. To truly appreciate a print created by either of these artists is to understand a little bit of their souls – this is the most subtle, most meaningful through line to two bodies of work I could ever imagine. Munch and Picasso feel like the oldest, most dear of my friends; I’ve spent my life with them.

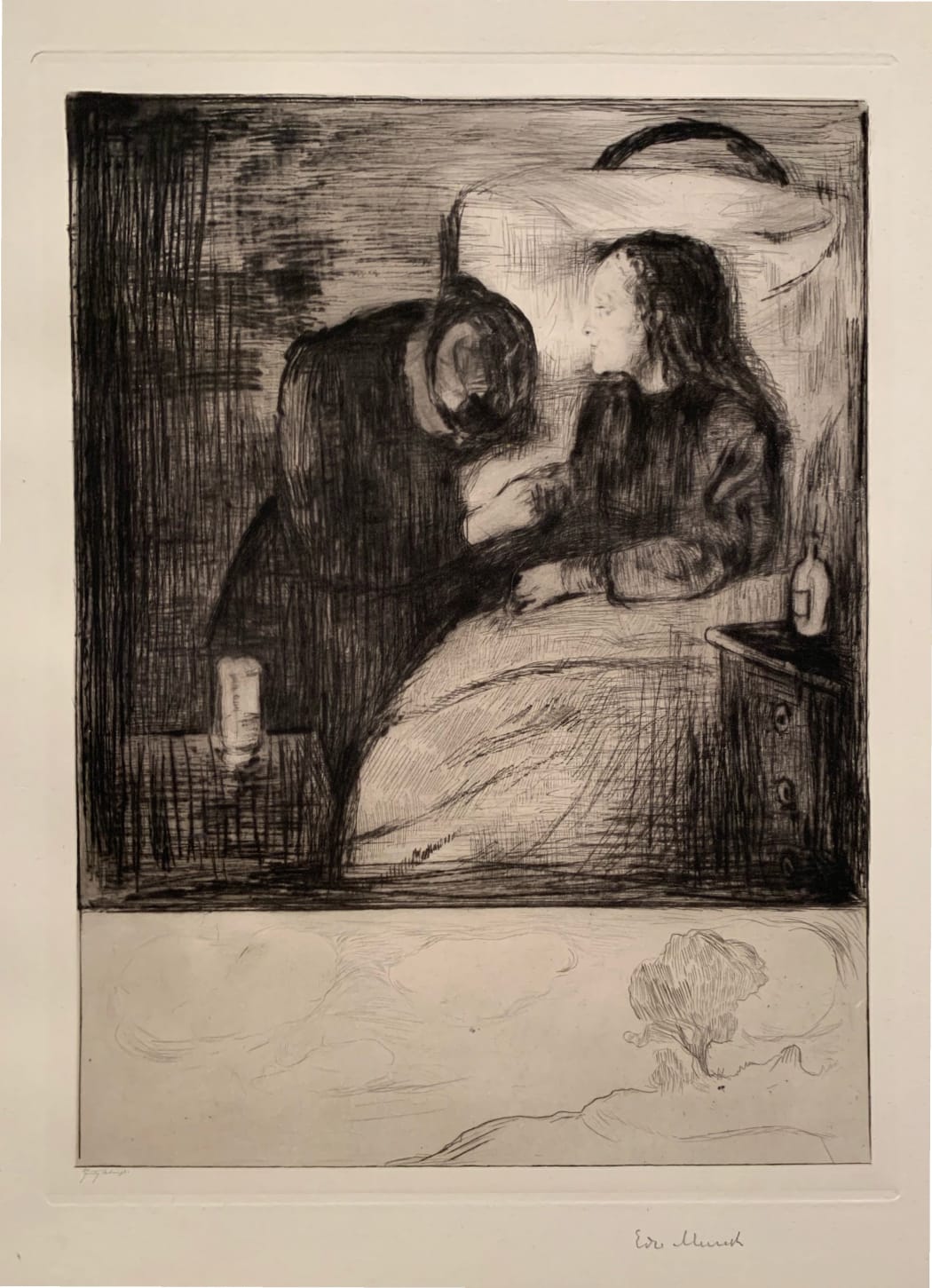

Of course, this is more true for some prints than others – or really, I should say, for some motifs than others. Some images occur so repetitively in these two bodies of work that it would be impossible not to have formed a relationship with them. As a prime example, one of Edvard Munch’s most variant and most recognizable works: Das Kranke Kind, more commonly known by its English name, The Sick Child. At this moment I am referring to W7, a drypoint made in 1894, at the beginning of the artist’s printmaking career, and very well received by collectors – though Munch did create four other graphic renditions. The image’s earliest iteration was done almost a decade before these; it is an 1885 painting, made at a time when twenty-two year old Munch was still under the tutelage of the Norweigan painter Christian Krohg, a Naturalist. The realistic sense of contemporary life is more alive in this work than in Munch’s more mythological images, those created down the developmental road of his expressive, tactile style. But even so – in the hazy atmosphere created by the drypoint thatching, in the protagonist’s drawn, fetal-like features, there is a shimmer of something else; a glimpse into a future mode of expression.

I’ve said that I love these prints for their diary-like nature, and The Sick Child is pulled straight from the bleeding memory of Edvard Munch. As a boy, his mother grew sick and passed away of tuberculosis. Munch was left with three sisters, a younger brother, and a father whose religiosity ironically was the wedge between him and his children. There was no comfort for young Munch in the wake of his mother’s death; reality was stark, cold; it is no wonder that he rejected the bleak plainness of its depiction in his later years. He became quite attached to his oldest sister, Sophie. Along with an aunt who came to stay with the children, Sophie occupied his mother’s vacated position. But again, warmth was snatched away from Edvard. In 1877, when she was 15, Sophie also became ill with tuberculosis. She was confined to her bed, no energy left but to turn her gaze to the window and stare out at the rolling fields of Kristiania.

Finally, when she knew she was near the end, she requested that her aunt move her to a chair. Edvard watched from the doorway as her thinned young body was picked up and settled in the chair, a pillow to prop up the frail bones of her upper back. From the amount of graphic iterations Munch would come to create of the The Sick Child, it is evident that the scene haunted him – his sister’s bloodless face washed out even in the dimly candlelit room; the amorphous clasp of her and the aunt’s hands; the aunt’s head bent, her shoulders curved in, already mourning even with life left. Long after Sophie died, long after he left Kristina and his father’s pious gloom, Munch would return, moving into a house near his old family home. He kept Sophie’s chair, positioning it near a window. The chair remained in the house even after Munch’s passing, and is today kept at the Munch Museum in Oslo.

It’s interesting – after W7, Munch returned to this heavy, harrowing moment several more times. And in each iteration, it seems that Munch’s memory focuses on something a little different: the slant of light as Sophie tilted her head just that way, the exhaustion-carved depth of her eyes holding the darkness. And in each, he takes a different technical approach to render the emotion. In W7, he worked on the drypoint plate directly, without the use of acid, enabling him to create a velvety rich darkness. This is apparent and so impactful to us, the viewers, in the blackness of the women’s clothes, contrasted with the paleness of his sister’s wan features; the fuzzy dimness of the rest of the room, as though smoked from Munch’s memory, contrasted against the blazing, unforgettable whiteness of Sophie’s infirmary linens.

As we journey on we’ll look at more ways in which Munch found himself expressing this memory. Until then, wishing you a safe and restful weekend.