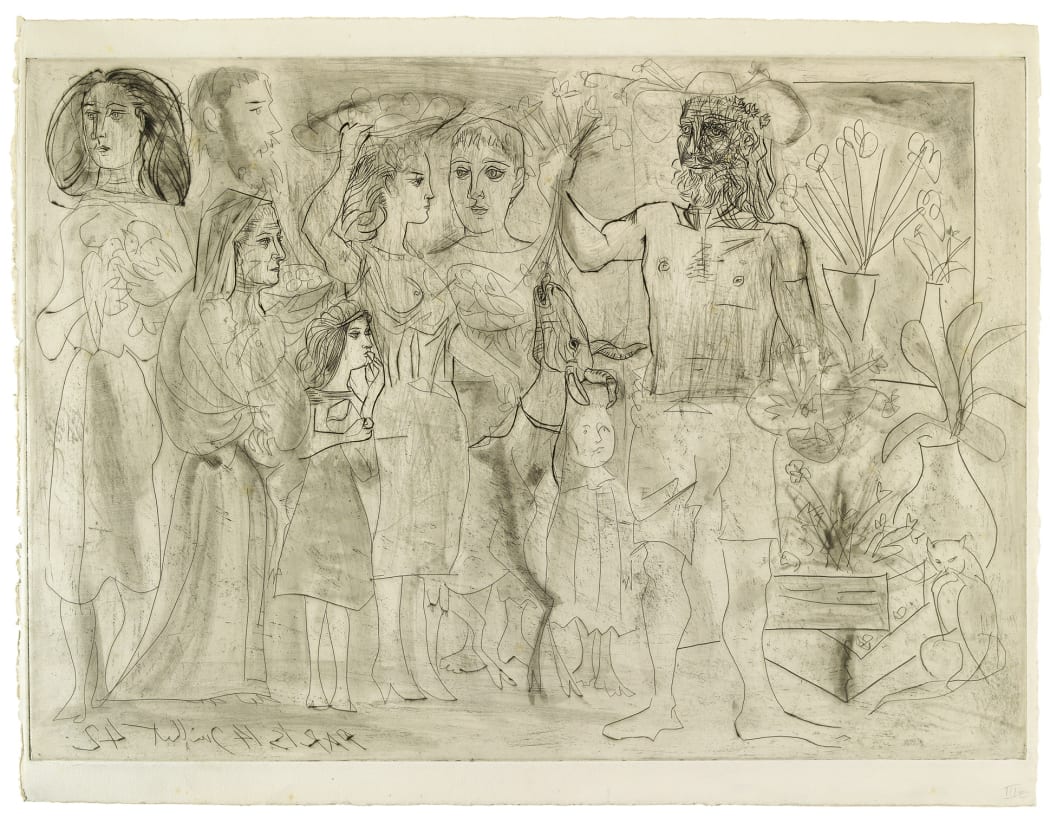

For the past couple of weeks, we’ve spent our time with the bulls, Picasso, and other surprisingly related friends. Today we’ll take a look at a print that will veer our course across the Mediterranean. On Bastille Day, in occupied Paris, 1942, Picasso created the aptly named etching Paris, 14 juillet 42 (Ba682), pictured above. It depicts a crowded scene of people, perhaps at the market or in attendance of a major event – it wouldn’t be surprising if they were meant to be on the outskirts of the Bastille Day parade, a procession held every year in Paris on the Champs-Élysées. Except that this famous celebration was not held at the time of this impression’s creation, during Paris’s WWII occupation; what’s more, the people are dressed curiously out of 1940s fashion. Really, they look much more like the citizens who might have instated Bastille Day back in the closing days of the French Revolution. So, what’s the story here?

It’s possible that, in one of the darkest moments of French history, Picasso wanted to focus on something more hopeful: peace. His model was a frieze of the Ara Pacis Augustae, a classical monument to the Emperor Agustustus’ “Pax Romana,” built between 13 and 9 BC. The altar was (unfortunately) erected in the flood-zone of the Tiber River, and thus through the ages was gradually buried under several meters of silt deposits. During the period Picasso lived in Rome (working on the set design for the Ballet Russes), the then-president of the Piedmontese Society of Archaeology and Fine Arts, Oreste Mattirolo, suggested that all fragments of the structure were to be collected and joined in order to rebuild the altar. This would have been huge news, inescapable by the classically-enchanted Picasso. But even if he didn’t have opportunity to witness any of the friezes while in the monument’s home city, he might just have easily seen them in his own; the Louvre has had a slab from the originally northern-oriented wall of the Ara Pacis in its collection since the late 1860s. And at this point, the tales of Picasso’s take-homes from that museum are as old as time.

The Louvre’s slab shows a line of people crowded together, traditionally interpreted as a sacrificial procession on their way to honor the Emperor. Interestingly, the sculptor included children in the scene; this would have been novel at the time of the altar’s construction, and is likely a tool used by the artist to evoke empathy – or, more precisely, to evoke themes of piety, morality, and family. Useful indeed, especially for a leadership looking to ease public tensions that Augustus’s regime would become dynastic.

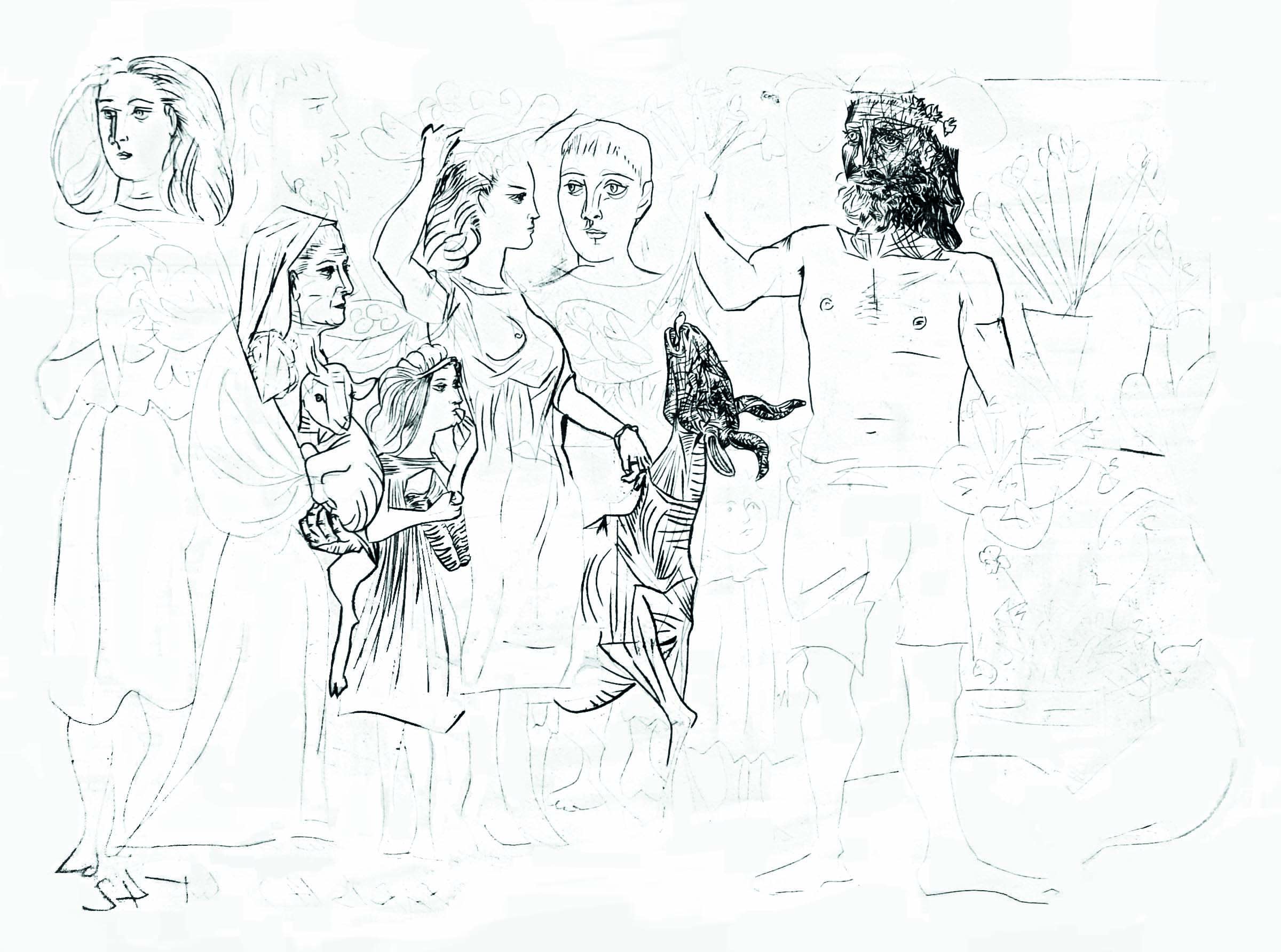

Paris, 14 Juillet 42 (Baer 682), 1962, lithograph, 17 1/8 x 24 3/8 inches

But I digress – back to modern times. The same procession shown on the Louvre’s slab and most of the originally-northern wall of the altar is present in Picasso’s Ba682. And curiously, Picasso also carries over the presence of children. However, Picasso’s cast of characters is a bit less anonymous than the original sculpture’s; his seem to be figures we have seen before, ones that map onto his life. There is the old woman in her shroud, perhaps representing his beloved mother who was not two years gone from the world; the bundle of doves, or maybe pigeons, a reference to his pigeon-loving father, also an artist; and the tall woman holding the doves, her flowing long hair predicting the classic motif of his soon-to-be lover Francoise, emblematic of the secret he once told her: “I painted you before I saw you.” Most prominently, there’s the bearded painter, taking the position of honor at the head of the procession (perhaps mirroring the Ara Pacis’s positioning of Augustus, or of the figure typically interpreted as Aeneas, a hero of Troy and the founder of Rome). This bearded man appeared during the Suite Vollard and would appear again, in the series of prints created at the end of Picasso’s life. Always, he represents the artist himself – the beard being a symbol for growing artistic authority, self-knowledge, life experience, but also a little bit of an irony, since Picasso never wore one himself. Like other of his famous narrative works (think Minotauromachy) the symbols add up – Bastille Day, the allusion to the Ara Pacis, a perhaps illusory message of peace in times of darkness, the children, the sacrificial goat, the doves, the artist – but they do not neatly figure out. And I think that makes this work a more interesting story.

Picasso’s graphic work and the Ara Pacis share one more formal feature: they were both done twice. Ara Pacis was reconstructed from its ancient pieces and installed on a new foundation, changing its original orientation; Picasso transferred an etching proof of Paris, 14 juillet 42 onto a lithographic zinc plate, enabling him to pull a lithograph without redoing the image. Though preserving the constructions of history is (thankfully) rather commonplace, Picasso’s experiment is the only known instance of a complete transfer between these two printing mediums. In the experiment, he pulled just three impressions – and one of them (pictured above) I am lucky enough to house in the gallery.

Thank you for joining me this week as we swept from Spain to France to Rome, and back to France again. From New York: until next week, warmly wishing you a pleasant weekend.