With Father’s Day coming up this weekend, I’ve been thinking about my own dad – my roots. Growing up in Budapest, my family owned a large paper factory. We were an old-fashioned family; my father headed up the factory, while my uncle did the marketing and financial management. And so it goes that our dinnertime conversations and discussions over long Sunday walks were about paper, our work and our interest – subliminal messaging, you could say, building the foundation for my brother and my different, at the time still distant careers. After World War II the Communist Party took over the factory, but my father was retained as lead engineer. When he retired, my brother was hired to replace him. Needless to say I took a different path, but when I found myself at its crux – that is, when I’d decided to become an art dealer – I could only think of paper. And here I am, a dealer of prints.

It happens like that – our early lives, our people shape us, even if we cannot see the shape as it is forming. Sometimes we do not see how it is we have been formed for years down the road. For Picasso, the shape was not paper, but pigeons. His father was an artist, a drawing teacher at Escuela Provincial de Bellas Artes in Málaga, Spain. He specialized in still lifes and landscapes, but his imagination was far more specifically regalled by images of doves and pigeons. Though himself no “Picasso,” he was dedicated to his son’s art education from Pablo’s first word – ”lapiz,” or, pencil. Years after his father’s death, in 1949, Picasso created a lithograph at Mourlot’s studio in Paris – it pictured a startlingly white dove, and it was called La Colombe. The image was used to illustrate a poster at the 1949 Paris Peace Conference and subsequently became a mid-century icon of peace. And though it was likely created with the Spanish Civil War more expressly in mind than the memory of his father, doves and pigeons are family – the Columbidae family, in fact.

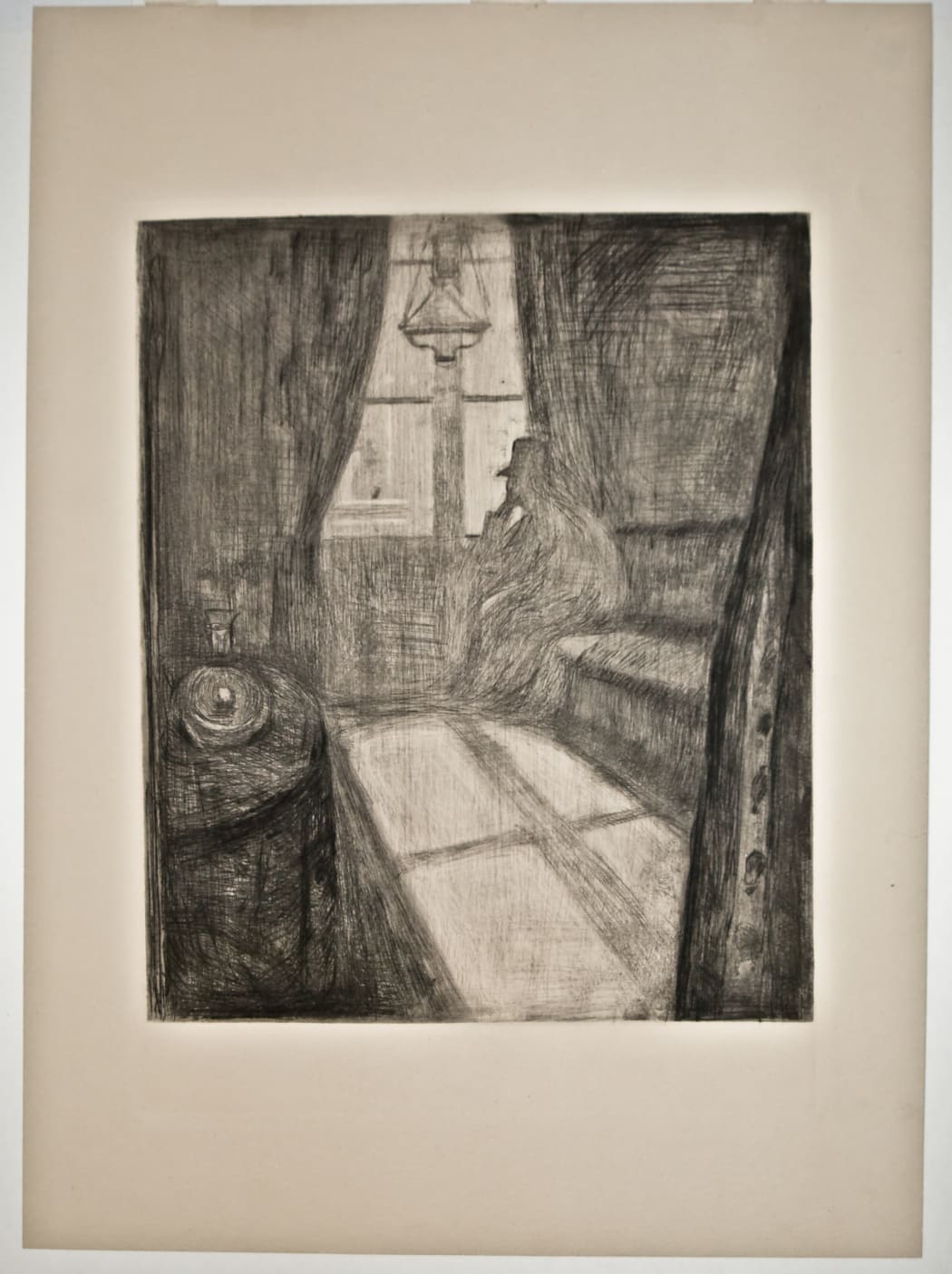

But let us not forget about our other friend, Edvard Munch. In 1889, Munch was living in France on a government-funded scholarship. Unlike Picasso, his father had not supported his choice to pursue art; he’d wanted his son to develop a more practical application of his technical skills. So Munch was on his own. Cholera broke out in Paris that winter, forcing Munch to find lodging outside of the city. He rented a small flat above a cafe in the suburb of St. Cloud, one that afforded him a view of the Seine. It is out the window and toward that river that the figure gazes in Night in St. Cloud (or, Moonlight W17), pictured above and first drawn in early 1890. The rich, shadowy interior of his room echoes the figure’s – presumably, Munch’s – interiority. He is isolated, and so consumed in thought that he seems to melt into his surroundings more than assert himself as a separate being. According to collector and Munch biographer Sarah Epstein, Munch’s mind is not on the pandemic so close at hand, but on the memory of his father.* He had passed away months before, and Munch had learned of the loss by letter. Suddenly, without the oppositional force his father had represented for so much of his life, Munch was confronted with his own identity, the smoky shape of himself. The relationship had not been one characterized by guidance or support, and yet it was hugely meaningful, ironically impactful to Munch’s career in art. His interests pivoted to spirituality and symbolism; he turned to his diary and wrote a phrase that has come to be known as his artist’s manifesto: “The subjects of paintings will no longer be interiors, with people reading and women knitting. They will be breathing, living people who feel and love and suffer.”**

With Munch’s words we close this week. A bit of an irregular mailing for Father’s Day, but perhaps a mirror for the individualistic ways we regard our fathers and father figures. Wishing all of you a wonderful weekend, and until next time.

*Epstein, Sarah. The Prints of Edvard Munch: Mirror of His Life (1983). (pp. 42)

**Gotthardt, Alexxa. “How to be an Artist, According to Edvard Munch…” Artsy. (2018)