There is an adage that goes, “No new ideas, only new things.” Audre Lorde had her own version, which I like better: “There are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt.” These words came to my mind a few weekends ago, as I was walking through the Met with my wife, Sabina. Without any real direction in mind, we had made our way south from the main entrance, toward the great old Greek and Roman Art. Just as we stopped at the end of the hall, planning to turn around, our eyes simultaneously fell on one piece of artwork. There was a beat, and then we looked at each other. We both had the same thought. “Picasso,” we said together.

Of course it was not an actual Picasso in the Greek and Roman wing. Before us was a horizontal sculpture of a man and a woman reclining (a klinē, Google tells me, is the ancient Greek version of the French’s chaise lounge, typically occupied during the after-dinner symposia). The sculpted figures gazed at each other, the woman’s head upturned to the man’s blunted nose and thick tangle of beard, and the man’s face beaming down at, well, nothing. The woman’s face was not carved out. Curatorial signage told us that the woman’s featurelessness was not a by-product of the sculpture’s years, but more likely because the man – which signage fairly presumed to be her husband – had predeceased her, and no one had bothered (or been around to) fill her face in after her death.

Marital injustices aside, I was struck by another aspect of the sculpture. The man cradled a long reed in one elbow and in her right hand, the woman clutched a sheaf of wheat and a garland. The presence of symbols of the elements, likening these two to semi-divine personifications (that is, gods), were not uncommon in the post-mortem figurations of the ancient elite that would have marked their places of burial. But what they recalled for me (a much more practiced appreciator of the art that came centuries later) was a subset of the Suite Vollard, which is the series of narrative — more accurately, autobiographical — prints Picasso created throughout the better part of the 1930s.

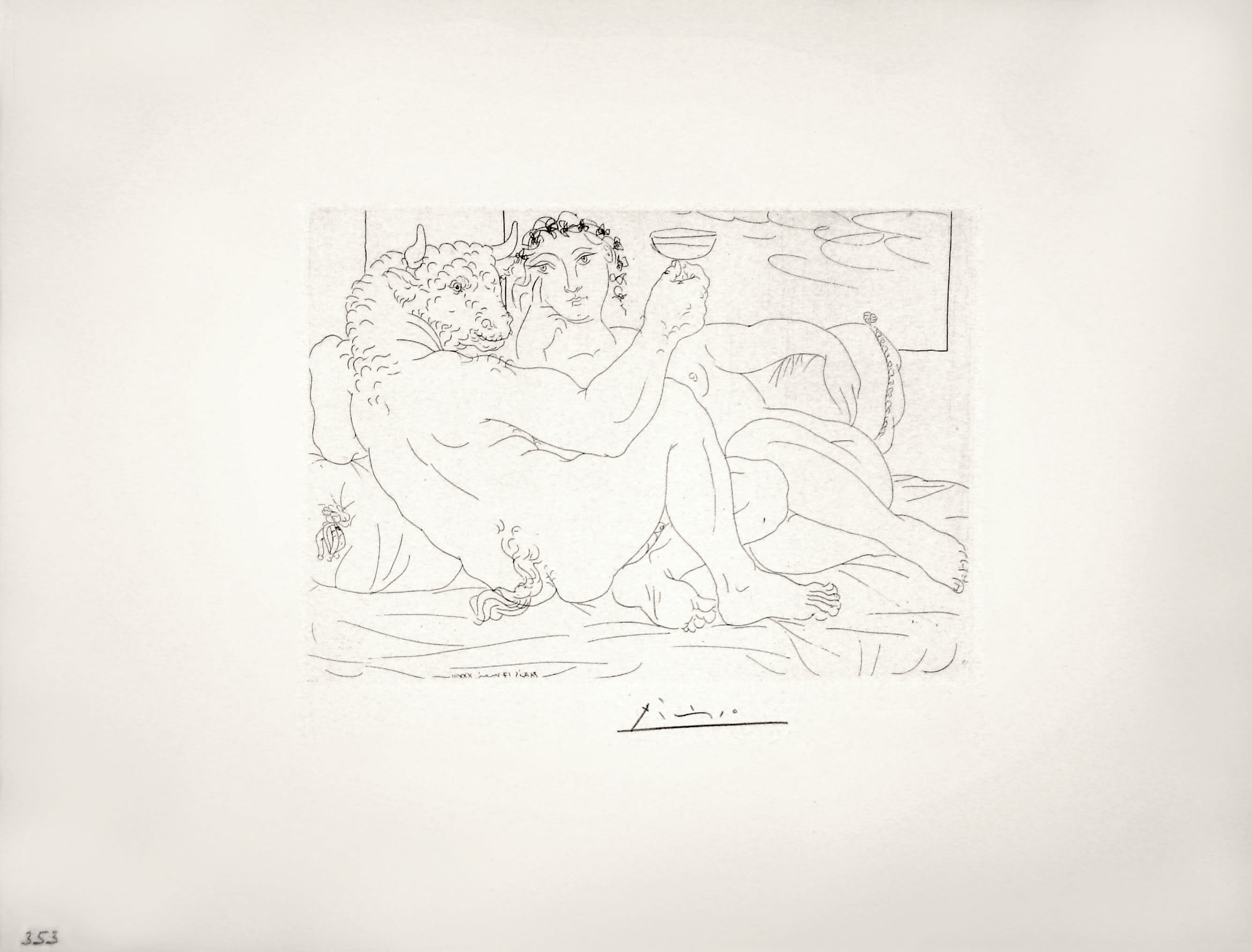

Le Repos du Minotaure : Champagne et Amante (S.V. 83) (Bloch 190), 1933, etching, 15 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches

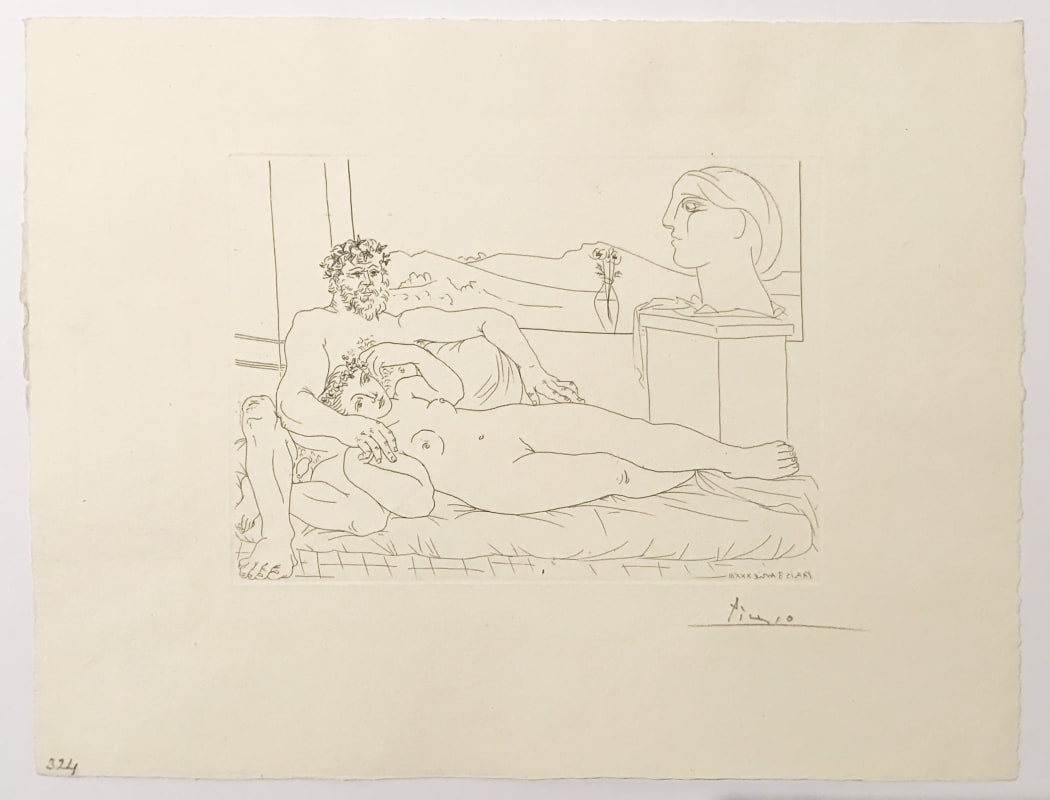

The subset I’m referring to is typically called the “Painter’s Studio,” as it plays out the story of a bearded, ancient-Greek-esque artist (read: Picasso), making pictures and love to his model. In the 1933 etching Vieux sculpteur et jeune modèle avec le portrait sculpté du modèle (B172), the resemblance between the Met sculpture and Picasso’s print is uncanny. The mythological man holds a woman (face intact) on a familiar reclining chair. The pair are overlooked by the face of another woman, mounted on a pedestal — yes, she is a sculpture. Instead of missing a face, she is nothing but a face. The connection continues in Le repos du minotaure: champagne et amante (B190), in which our leading man the ancient artist has morphed into the Minotaur, that creature of Greek mythology which haunts the Suite Vollard as though placed into a new labyrinth with updated, modern interiors. Poised in the Minotaur’s hand is a chalice, which, like the water reed in the sculpture, is a traditional symbol of the water element; and placed atop the woman’s head is a crown of laurel, an earthy symbol remnant of the sculpture’s garland and wheat.

Am I attempting to claim that Picasso saw this very sculpture and raced back to his studio, alight with inspiration? Certainly not. But Picasso’s fruitful ventures to art museums are well-told. We know, for example, how many ideas stemmed from his strolls through the halls of Iberian art at the Louvre. His visits to these exhibitions and fascination with their displays of ancient masks have been (perhaps a bit too neatly) tied by biographers like John Richardson with his creation of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), which features ladies with the same elongated faces and hollowed eyes.

More important than playing guess-who on the history of these works is the magic of stumbling into a connection that you were not expecting to make. Had Sabina and I not known those Picasso images so well, we probably would have kept walking down the hall. Instead, we were gripped by the devotion eternalized between the sculpted figures, who had decided to stay together even after life; the similarities between the ancient and modern artworks served to illuminate the love between Picasso and Marie-Therese, his Suite Vollard muse, in a new way; and we were reminded of ourselves, too, together for thirty-six years. In moments like that Met experience, I am thoughtful of art’s power: it can trouble the fraught lines drawn into our imaginations by history; it proves that those very imaginations are connected, growing from one another, unbound.

Until next week, when we can joyfully look at some more.