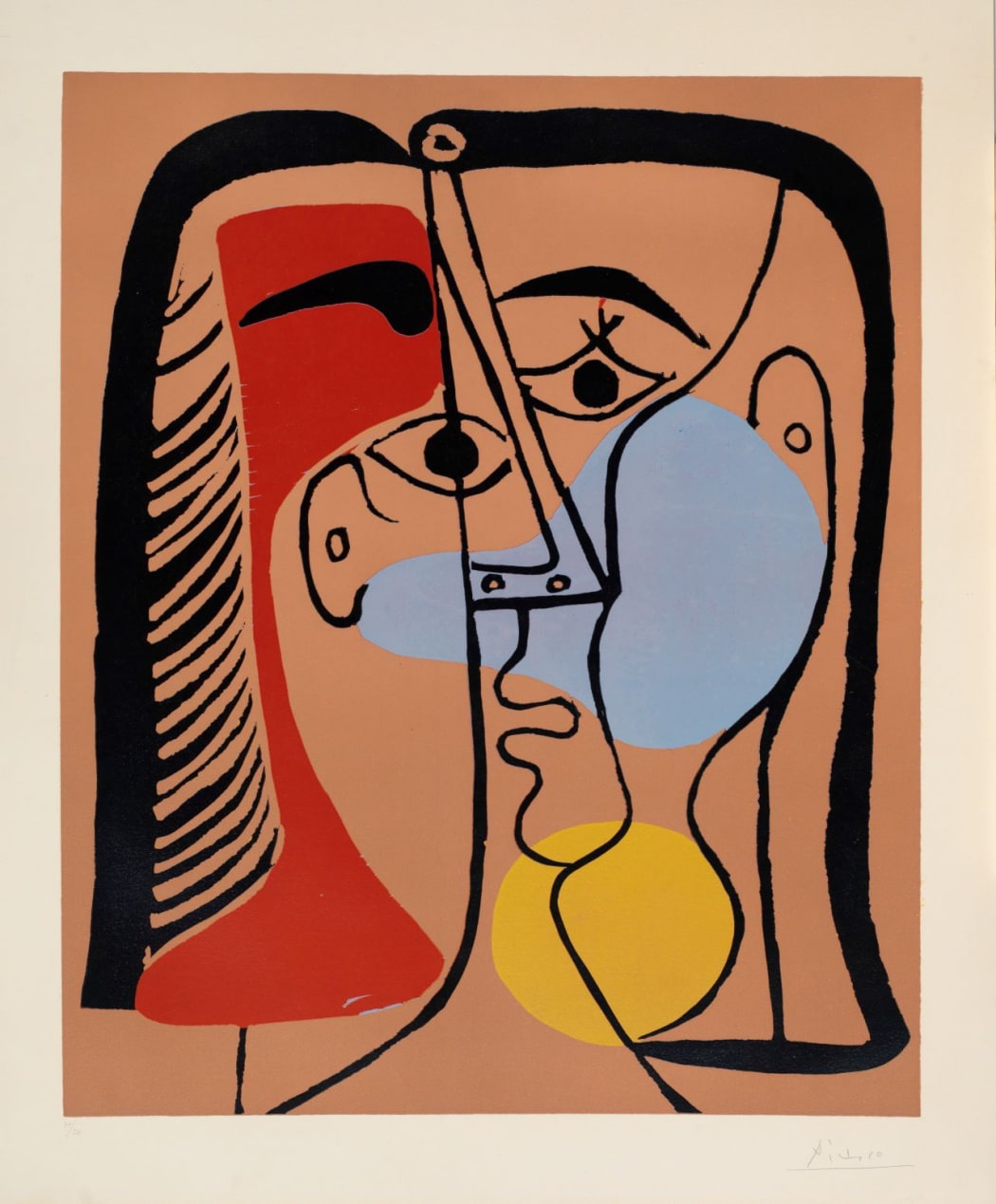

Last week Picasso stumbled across Hidalgo Arnéra’s printmaking shop while in Vallauris, working on his pottery craft and enjoying life with Jacqueline, away from Paris. There, he learned about the possibilities of a new technique – one that necessitated much less fuss than lithography and etching, which had required him to courier stones and plates to faraway studios. There is carefree Mediterranean warmth and joyous, playful linework in prints like Portrait de Jacqueline aux cheveux lisses (B1066) – above – and Portrait de femme a la fraise et au chapeau (B1145) – below – showcasing Picasso’s inclination for his new skill, the way it seemed to complement the sunning, behatted visages of his post-Parisian life. Of course, there is also color – color used in a way that Picasso only rarely did before in his prints. The history of Picasso’s colored linocuts is a notch in his master printmaker belt – a canto in the tale of his constant reinvention of printmaking techniques.

The story begins with Picasso’s first published linocut, B859, created in 1958. The image is a modernization of Lucas Cranach the Elder’s famous painting, “Portrait of a Woman” (1564). Picasso stayed quite true to the original — he retained the shadow behind the subject, the corner of curtained backdrop — but took his own liberties with color and shape. Some people say that, in true form, he replaced Cranach’s subject’s face with the unmistakable features of Jacqueline — a believable fiction, if it is one. Though it was a vibrant and widely successful use of a new palette, and is today a print admired, in Picasso’s mind the print’s value was in its challenges.

And the primary challenge he’d faced was in the registration of color. Through all the states he created of B859, he’d had difficulty with it; each color used in the print corresponded to a different sheet of linoleum, which meant that he needed to cut several sheets with the reverse of pieces of the overall image. It was a time-consuming process, tedious. And it would produce a color registration that was less than clean-cut, at that. To reduce the time needed to lay the color, and to enhance the cleanness of the registration, Picasso thought of a shortcut. the “reduction” technique – one credited to his invention and that was cultivated with the support of his printer, Arnéra.

In simplest terms, he found a way to use only one sheet of linoleum on which he could lay down color sequentially, starting first with the largest area and ending with the smallest area. Throughout the process, the surface of the linoleum would be cut down, so that at the end just a very small bit of material would remain – the last color printed. Because the cut-away parts get discarded, there is no way to correct mistakes; the printmaker has one shot. Perhaps it was the thrill of this task, the masterful facility it required, that incited Picasso’s early 1960s spree of colored linocuts.

In any case, the happy result are images like B1066, in which primary color bubbles up like bloom in Jacqueline’s cheeks, like the sun glinting off of one side of her face; and B1145, in which color becomes the planes of her face themselves, her face stamped into Picasso’s imagination in light. It is the deceiving simplicity of these images, their ease and iconography, combined with the inventiveness of the artist which has raised them to a status of genius.

But as always, there was more innovation ahead. Next up, he’d find it in the bathtub. More on that next week.

* Lieberman, William S. Picasso Linoleum Cuts: The Mr. and Mrs. Charles Kramer Collection,

(1985) (pp. 11-12)