When we last left Picasso, he’d had a recent vacancy in the role of muse. Today, we explore a print that enacts Picasso’s feelings about Francoise’s departure, L’Italienne (B740) – though at first glance, you might not see Francoise or Picasso in the print at all.

A brief bit of background, to catch us all up: Two of Picasso’s largest, most impressive sugarlift prints showcase the end of his most challenging relationship. The first, La femme a la fenetre (B695), was created in the spring of 1952. It shows a soft, ambiguous Francoise, no longer as electrified and present as she appeared in earlier renderings. In B695, her despondency is still potential, underwritten; there is enough feeling left in the relationship to keep her at the window, rather than on the other side. The second, L’Egyptienne (B746), created a year later, is anything but “ambiguous.” Francoise’s face is twisted, indecipherable. There is ineffable pain between artist and subject, painful history. The relationship was over. Our studied print this week, L’Italienne, was completed a few months before B746, in January 1953. Picasso, Francoise, and their two small children, Claude and Paloma, had been splitting their time between the country and the city, with Picasso in considerable favor to the former, and his mistress to the latter. Despite his geographical preference, Picasso needed to extricate himself from family life; he traveled north, to Paris, presumably to visit his main atelier, which was still Mourlot’s – the legendary station of lithography.

One afternoon at the workshop, Picasso noticed a pile of zinc plates lying forgotten in a corner, having waited years to be polished out. He stooped to examine the plates one by one. The great artist’s fascination with such presumable byproduct was amusing to the Mourlot workmen – they’d figured these plates unusable. Of course, their dismissive attitude was an open challenge to Picasso. When he finally stood, he’d settled on a plate. It came home with him that night.

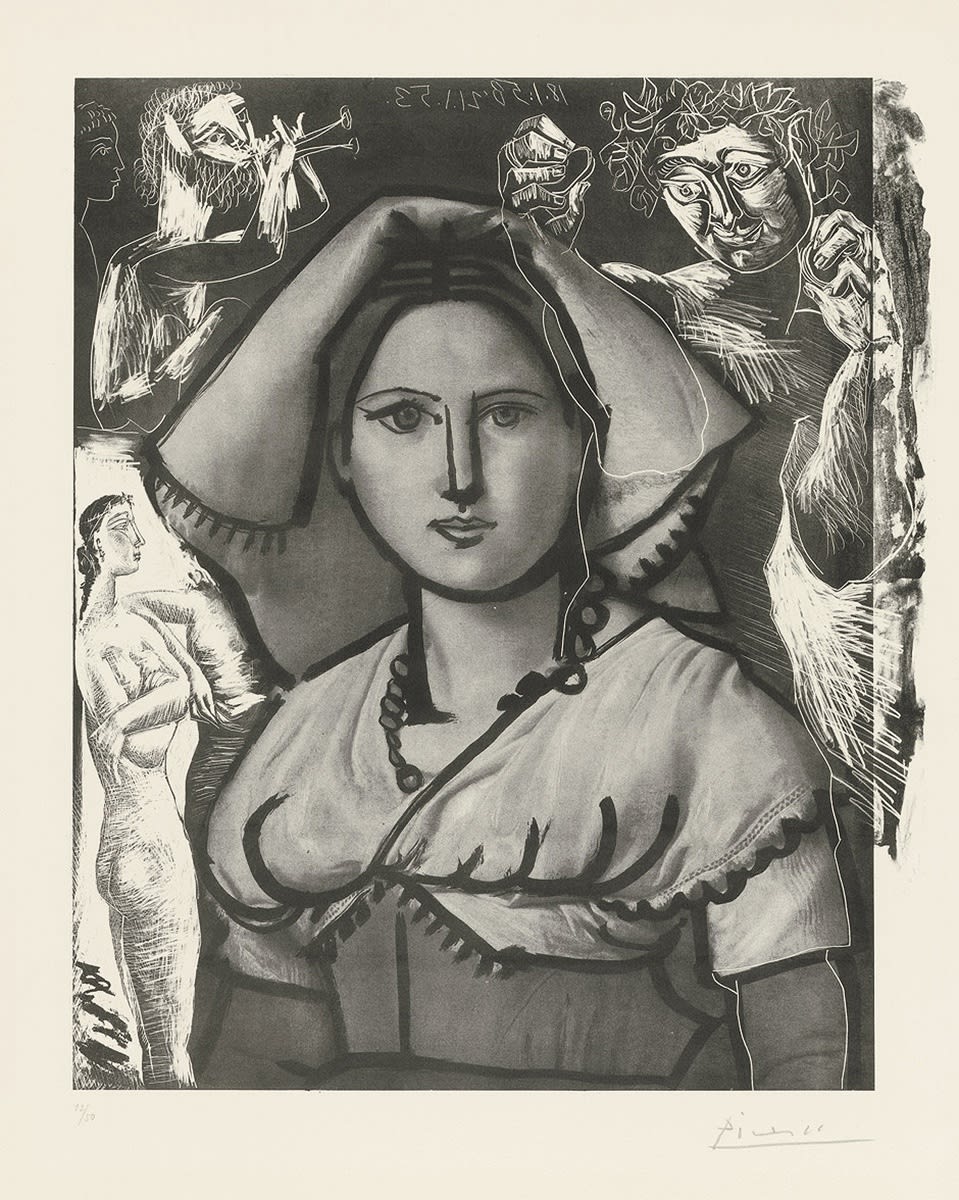

The plate Picasso selected had originally been used to print a poster for an exhibition at the Tuileries Orangerie, back in November 1948. It showed a reproduction of Portrait de jeune italienne (Vittoria Caldoni) (c. 1825-6), a work by the Lyons painter Victor Orsel.* Ms. Caldoni, the subject of Orsel’s painting, wears a rustic dress, a tight bodice, and crisp linen headpiece. She stares rather submissively over the viewer’s right shoulder – though this must have been a choice by Orsel, for Ms. Caldoni was no stranger to the subject’s seat. She’d been a popular model with German artists studying in Rome, especially those involved in the 19th Century Nazarene movement. Why so popular? Perhaps it was her Madonna-esque likeness, her rather Biblical presentation.

Whatever it was, it caught Picasso. Over the next couple of days, he recycled Orsel’s portrait. He used a wide brush to outline her face and clothing. He redirected her passive stare so that she gazed unabashedly at the viewer – and it is here that we begin to see Francoise, whose early lithographs were so characterized by her potent, full-frontal look. Continuing the parallel, Picasso enlarged Ms. Caldoni’s eyes and smoothed her face into an animated oval. But his invention did not stop there. He expanded the story of L’Italienne’s resurrection into the background, adopting a mythological style remnant of the Suite Vollard. A jovial satyr trumpets her return; a laurel-crowned god locks eyes cross-page with a flushed, naked woman – he is virile and she is blooming, creation is imminent. These background characters signal Picasso’s long-grown frustration and his eternal desire; they play out Picasso’s own resurrection, as he imagines himself stepping out with another woman in front of (or, just behind) his young mistress.

When they saw what Picasso had done, the atelier was amazed. Miraculously, he had brought the dead plate back to life, bestowed new life upon it. In fact, some viewers say that they recognize the woman to L’Italienne’s left, with her thick dark hair pulled back at the nape of her neck, and her profile defined by a long, straight straight nose – they recognize her as the woman who would become Picasso’s next muse, Jacqueline. More on her in the weeks to come.

* Manchester, Elizabeth. PhD. “Bloch 740” (September 2012).