Last week, we examined the Sculptor's Studio theme of the Suite Vollard. In it, Picasso worked out the dynamics of his mid-to-late stage relationship with Marie-Thérèse Walter – among other nuances, some visible to the art critic or appreciator in-the-know and others lost to history. The majority of the plates comprising the Suite’s one hundred completed images were made in this same period, successively, almost compulsively – as though Picasso’s thoughts and feelings of the moment were swollen balloon-like in the cells of his fingertips; burst, released, they seared into the plate and pulled onto the page. These images are the diary of one with little use for words; they are an imagistic projection of his internal life. And while the Sculptor’s Studio presents something very serene, very beautiful, another series captures the darker side of interior life. In the five images comprising what is sometimes called the Battle of Love sequence, Picasso treads the troublesome terrain of representing sexual violence.*

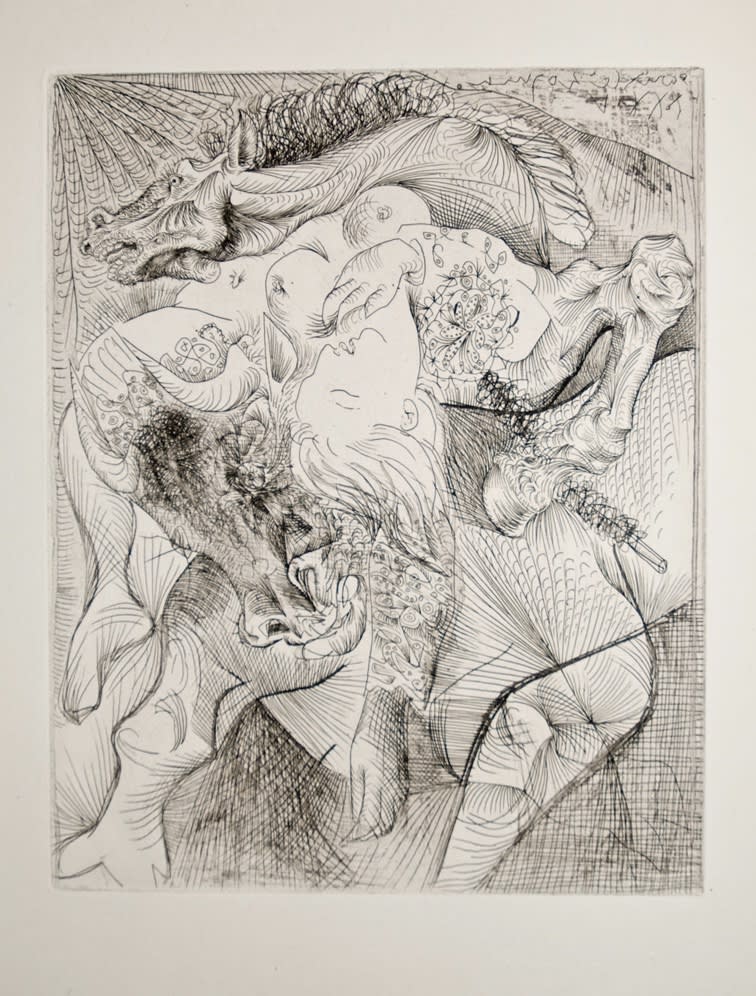

On this, one of Picasso’s most recognizable, most provocative artistic preoccupations, the great curator and critic William S. Lieberman astutely wrote that “the cinematic moment of the conflict interests him most.”** This statement is embodied in one of the most emotional etchings within the Suite Vollard, Marie-Thérèse en femme torero (B220), created in the summer of 1934. The heat of the summer shows itself with force; the movement and tension in the image are as tangible as the brutalized subject’s crushed body. As the title suggests, in this image Picasso imagines Marie-Thérèse as a female torero, thrown from her thrashing, agonized horse and strewn across the brawn of the bull who attacked it. Marie-Thérèse’s exposed breasts, posture, and breathless expression do not speak to the context of the bullfight; these details instead imbue the work with a sexual quality. The animalistic aggression, the gore of the bullfight is translated into fraught longing, human pain.

Bullfighting was fresh in Picasso’s mind at the time he etched the plate for B220. As he did many summers throughout his adulthood, in 1934 he took a trip to his native Spain, birthplace of the bullfight. Though why the bullfight stuck in his imagination might have had more to do with the climate than the sport. Spain – two years shy of its civil war – was politically broiling; “fanatical clergy and an aristocracy of large estates” were embattled by a restless Left. It was not a comfortable place for a sensitive, expressive artist; Picasso used to say of pre-WWII Spain: “[they] would have burned Cezanne alive.” The sociopolitical tension in Spain echoed throughout Europe. In February of 1934, Hitler (already Chancellor for a year) flexed his power in Germany, the Reichstag burnt, and France too felt the violence of the extreme Right. On June 30, ten days after Picasso created the plate for B220, Hitler conducted “The Night of the Long Knives,” a mass killing of at least eighty people (though likely hundreds more), and one of the first of Hitler’s dealings that sent ripples through the surrounding democratic countries.*** Familiar to those living in (or concerned with) America today, there was a deep tension in Europe’s atmosphere — a comparable tension to the one between the bull and the torero in the ring.

Other artists of the period made good use of the bullfight ring. Ernest Hemingway, a maker of modernism a few decades Picasso’s junior and an expatriate writer captivated by the allegorical nature of the fight, famously understood the bullfight as the most perfect analogy for the relationship between the artist and their work. He wrote: “Bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death and in which the degree of brilliance in the performance is left to the fighter's honor.” Hemingway saw the artist as both the bull and the man, and the fight – in all its fury, its feeling, its creation and destruction – as the artwork. In Marie-Thérèse en femme torero, Picasso showcases a similar understanding. His most beautified subject, his Marie-Thérèse, is violated; the scene created is, in these words’ truest meanings, both dreadful and stunning.****

The final, perhaps most pertinent question: why would Picasso place his beloved in such an unsettling scene? “By his life and work,” wrote critic and good friend to Picasso, Pierre Daix, “by the transformation he effected, Picasso proved that art in the Twentieth Century, like the sciences, had become multifaceted. Beauty was no longer the single solution to a unique problem, but numberless explorations of numberless impulses from the vast unknown.”***

We will meet you once again next week, for more prints from the Suite Vollard.