Let’s zoom ahead from Edvard Munch at the turn of the 20th Century and return to the age in which we’d bookmarked Picasso. He’d been taken up in a whirlwind of culture – high art, celebrity, increasing wealth and reputation – landing him in a marriage with a Russian ballerina who danced with the Diaghilev ballet company. Olga was traditional, upright, and wanted Picasso to be her match. This motivated her marital sifting out of his, by her estimation, less sophisticated acquaintances (and personal behaviors). With their departure, the ever-youthful, rambunctious spirit which had fueled the artist’s creativity was tampered. The forty-six year-old Picasso was starting to settle into this more conventional lifestyle when, one January afternoon in Paris, ambling past the Galeries Lafayette, he saw something – someone – special through the high windows. He stopped in his tracks. Life, and art, would never again be the same.

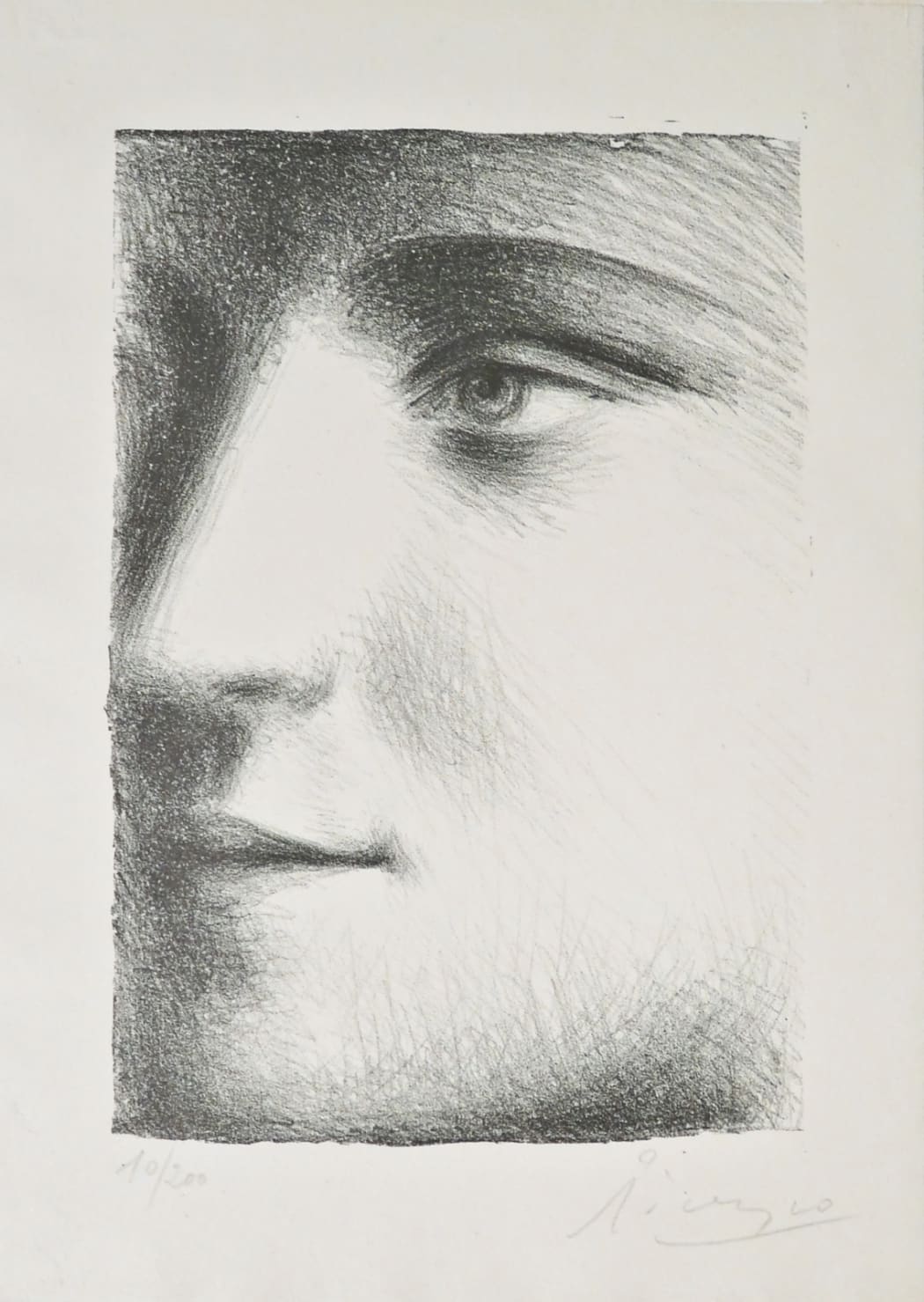

The experience is captured by Picasso’s lithograph Visage de Marie-Thérèse (B95), created one year later. The softness of that image, its close, intimate crop, speak to a catching glance – an ephemeral moment molten in the memory of the viewer. The subject is magnetic. She is the woman Picasso waited for outside of the Galeries. When she emerged, he approached her and said, “Mademoiselle, you have an interesting face. I would like to paint your portrait.*

Marie-Thérèse was seventeen that afternoon. She had no idea who Picasso was – though she could tell he was someone of worth from the quality of his tie, a black and red one that she would keep as a personal possession for the duration of her life. By her account, Picasso took her for a coffee, for a bite, and then to his studio.* There, as he would continue to do through the prolific fourteen years to come, he studied her face.

Though it is hardly revolutionary to write that Marie-Thérèse Walter unexpectedly awoke something important, something dormant within Picasso, her influence on the artist’s oeuvre is imperative to understand as it is so plain to see. She appears frequently, sometimes with lucidity, as in B95. But more characterically, Picasso lent her simplistic nature and classic form to more abstract representations, in which he was inspired to play with space and mythology in new ways. In all images of Marie-Thérèse, the viewer’s attention is positioned around her striking body and face. She was a natural athlete – a rower, cyclist, gymnast, swimmer, climber – and her robust form paired well with an innate physicality, as well as a languorous and simplistic grace, and a strong, stately Grecian profile.

It was this visage that came to touch everything. From the moment outside of the Galeries, she had seeped into Picasso’s artistic consciousness, and she breathed life into each of his new creations. And yet – their relationship was a secret; enjoyed by no one but themselves, suspected by many, and concealed as best they could from Olga. For Picasso was married, a father, and his family’s reputation would be at stake should the illicit couple be made public. Initial images of Marie-Thérèse were cast under this umbrella of secrecy, anonymously attributed.

The revelation was inevitable. The artist had a new, distinctly blonde muse, and his reinvigorated style was vivid with artistic fever. It could not stay anonymous for long.

*Widmaier Picasso, Olivier. Picasso: An Intimate Portrait, Tate Modern (2018).

** Finn, Clare. “The golden muse…” Apollo Magazine, Vol. 173, Issue 587 (May 2011).