The art critic Peter Schjeldahl once cheekily wrote that “we” (a many-encompassing two-letter word, presumably signifying all the appreciators of his art) “needn't live with Picasso, thank goodness, but only brain surgery could stop him from living in us.”* Never do these words come to light more than in Picasso’s 1952 and 1953 master prints, La Femme a la fenetre (B695) and L'Egyptienne (B746). These are two of the largest sugarlift prints in Picasso’s oeuvre — among the largest aquatints of his career. And their magnitude is just as impressive in scale as in emotional depth. The pair of prints tells its own story – I’m just here to relay it to you all.

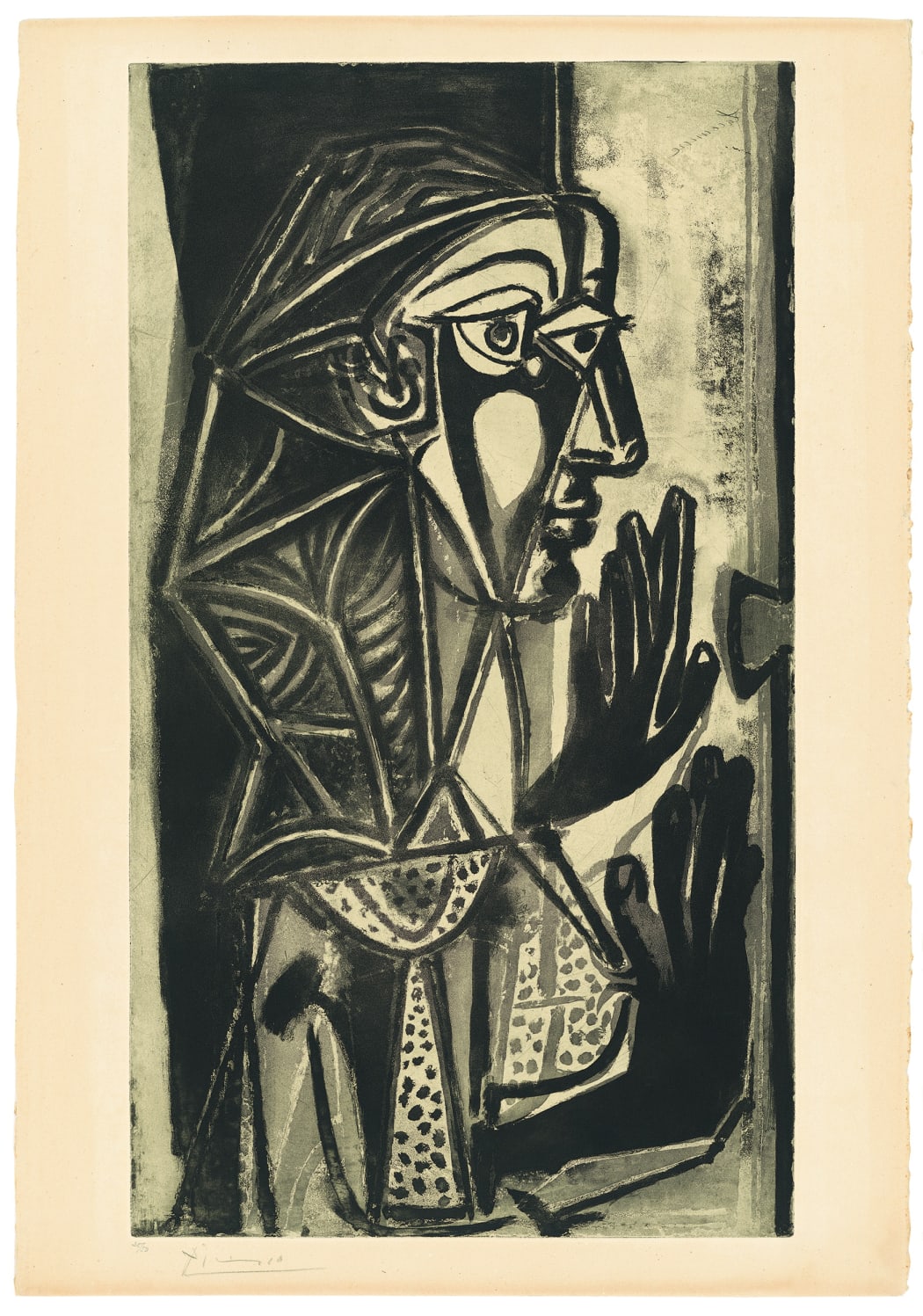

Francoise Gilot, the subject of these works, was an appreciator outside of Schjeldahl’s “we;” she did live with the artist. She lived with him as his lover, the mother to two of his young children, and as an intellectual and creative partner – a different status than the other muses of Picasso’s career. By May of 1952, the relationship had long-since hardened; her face in Picasso’s portraits had shed the warm, organic ease of its lithographic manifestations. Above, in B695, it is cast and carved like pottery, her expression left up to the interpretation of the viewer. Is her soft smile that of contentment, is she relishing the spread of soft light across her cheekbones, beamed in through the pane in one view, and the gaze of her love in the other? Or – is that same smile something more like despondency? Read the other way, the portrait’s focal point flashes downward to the shadows on the backs of her hands, her hands pressed into the glass of the window as though she is longing to be on the other side of it. Is she taking in the sensory pleasure of the world outside, or is the glint in her viewer-adjacent eye actually pearly, distant, glazed over? In showing her plainly, Picasso shows us her entirety; Francoise’s is the emotional ambiguity of reality. Should I stay, or should I go? Even as the question’s subject, Picasso captures its vestigial presence.

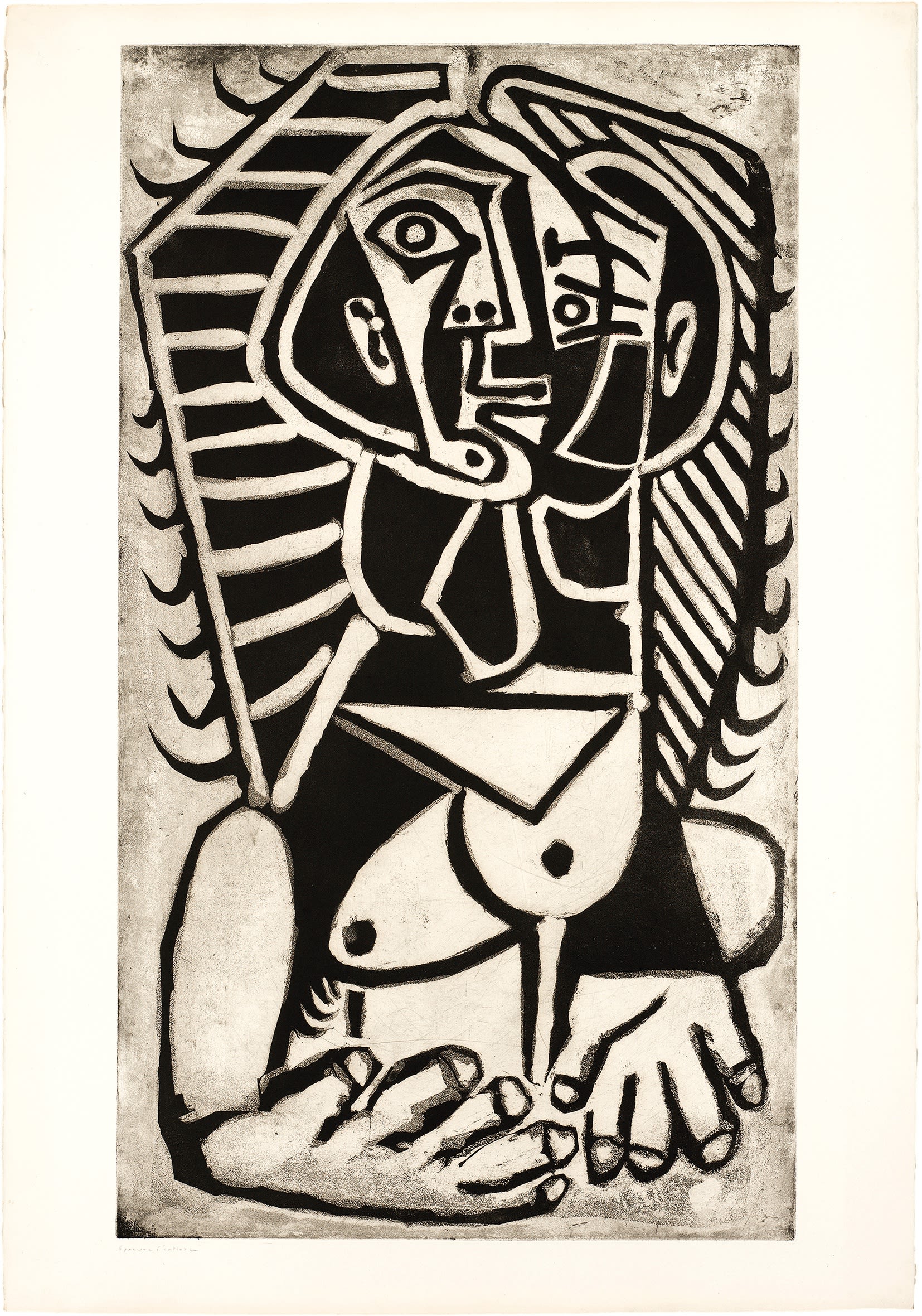

L'Égyptienne (Bloch 746), 1953, Sugarlift aquatint, 32 3/4 x 18 3/8 inches

Almost exactly a year later, in May of 1953, Picasso created one of his last portraits of Francoise. There is no softness left for her, only the stark contrast of black and white; no depth left either — she is two-dimensional, all sharp geometry. Even her usually-flowing hair is shown as thorny, thickly slicked to the sides of her fractured, disrupted face. It’s a face transplanted from B695 but rearranged, rendered with pain, less empathetically, as less human. If you are sensing conflict, you’re onto it. Francoise had become a hieroglyphic to Picasso, and vice versa – frustratingly, furiously, the channel of meaning between them had been lost. “There was no longer a real dialogue,” Francoise wrote in her memoir, published just a few years ago. “Each of us carried on a monologue in the direction of each other.”** By September, she left with the children for Paris. It was over.

Picasso rarely named his artwork past that of basic nouns and action verbs. The descriptive title of B746, L'Egyptienne, was not concocted by him, but by his printer at the time, Roger Lacourière. Lacourière found a striking resemblance between Picasso’s depiction of Francoise’s hair and an Egyptian nemes headdress – a striped cloth worn around the head, tucked behind the ears, draped over either shoulder. This garment is usually seen in hieroglyphics of deceased pharaohs. Lacourière’s comparison heightens Francoise to an imposing, important stature, though plants her firmly in the past; the historical one, and Picasso’s. It is a succinct and apt summary of the relationship’s end.

Of course, Picasso was never without a muse. A new woman would mean a new phase, a new way of seeing the world – a renewed means of expression. Along the course of his relationship with Francoise, Picasso had taken to longer bouts away from Paris, south, often in Vallauris. It would be this place that served as a new foundation. On this, I have more new prints to show and stories to tell in the coming weeks.