One of Picasso’s most famous proclamations is, “I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them.”* His choice of the verb “paint” could be naturally expanded into a multitude of other creative actions: draw, sculpt, etch. This simple sentiment seems to underpin the fine art of Picasso’s contemporaries and followers, the modernists – and yet, it directly conflicts with another artform that was so formative to this era and, ironically, integral to the transfiguration of Picasso’s style during the periods of voracious creation that studded his career.** I am talking, of course, about photography. Photography (at least, in its inception) claims to capture objects as the eye behind the camera sees them; frozen in motion, the photograph reveals exactly what the object is.

The reconciling connection between Picasso and photography is deceivingly simple – he was a more than willing and quite frequent subject. In Laura Mulvey’s influential work in cinematic theory, she upcycles a Freudian concept and puts it in updated terms: “There are circumstances,” she writes, “in which looking itself is a source of pleasure, just as, in the reverse formation, there is pleasure in being looked at.” Mulvey names this pleasure “scopophilia,” and immediately we can identify that Picasso seemed to have a severe case of it.*** Though Mulvey is discussing film, she might as well be describing the dialectical relationship between artist and model – a dynamic that Picasso dominated when he embodied the artistic eye, and one that surely inverted when he was in front of the camera.

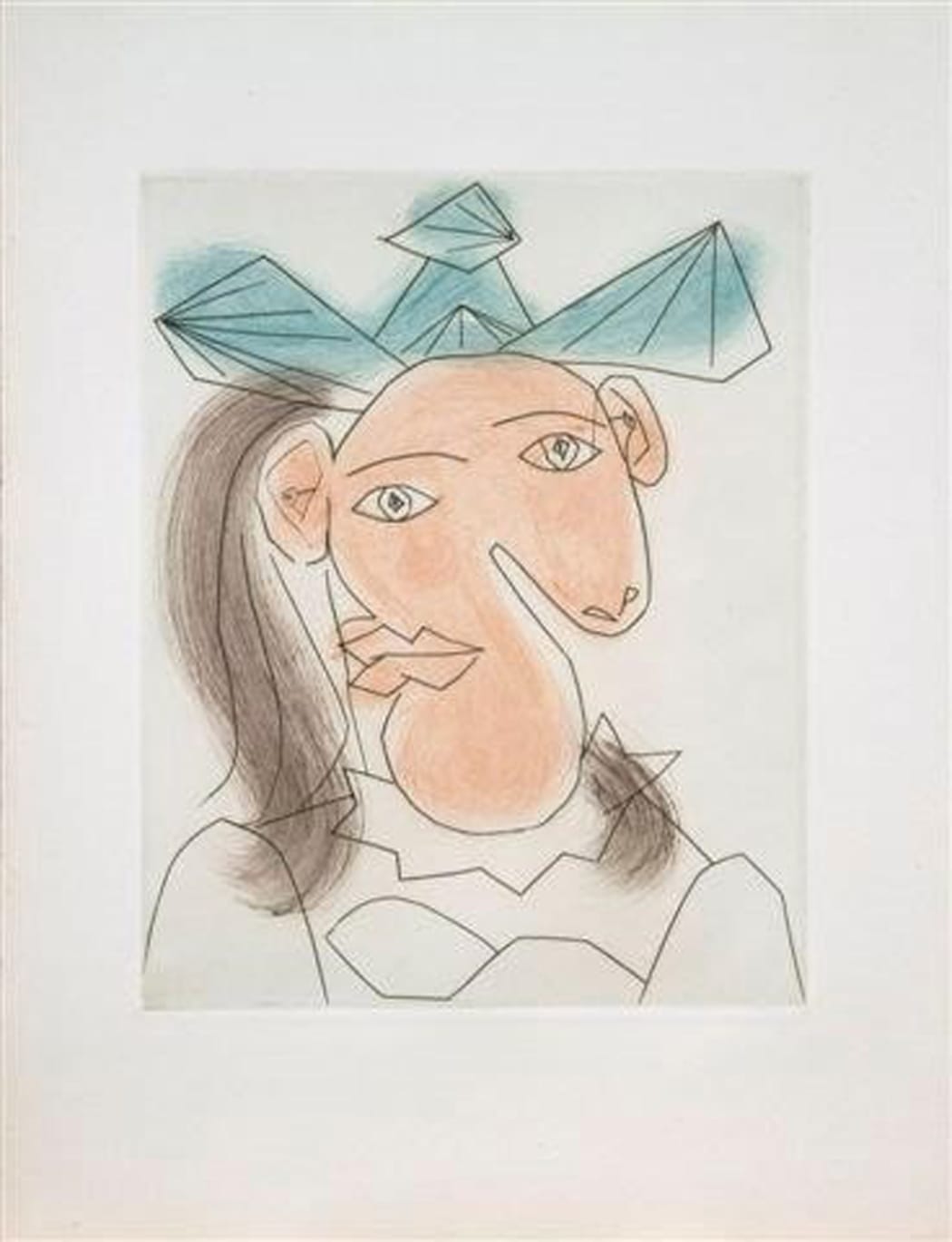

Picasso’s portraits were taken by photographer friends (among them: Rogi Andre, Brassai, Robert Capa, Man Ray, David Douglas Duncan, Lee Miller, Edward Quinn) throughout the periods of art that cropped up along the long course of his artmaking (the avant-garde, Surrealism, the advent of the modernism) – but some were taken by Picasso himself. Who can forget twenty-something Picasso, posed in his studio in front of his camera backgrounded by his artwork, straight-backed and arms folded across his bare chest in nothing but a pair of white shorts, boxer-style? One of the first photographs attributed to Picasso’s eye is called Portrait of Ricardo Canals, taken in Barcelona in 1904. It is a portrait of Picasso’s eponymous friend, who was a painter, photographer, and, pertinent to our interests, an etcher. In fact, Canals played a contributing role in Picasso’s introduction to etching, the happy result of which being works like Le Repas Frugal (B1) – a good start for a beginner, to say the least.**** For Picasso, photography and printmaking share a common ancestor.

Last week, we broached the dialogue between photography and Picasso’s prints by way of our introduction to Dora Maar (you can read that here). Dora was his roughly ten-year lover and during this time, his incessant photographer. In the spring of 1937, she spent two months photographing Picasso’s creation of Guernica, in effect documenting his creative process from the outside looking in. (Rather the opposite of the Suite Vollard prints, which show this same process from the inside looking out.) During their isolated time together during the WWII occupation of Paris, she created some of history’s most intimate pictures of Picasso. Interestingly, her portraits of her lover are rarely erotically charged, especially those taken at the beginning of their relationship, when Dora took her photos at her studio on Rue d’Astorg.***** In these images, Picasso’s presence alone carries a good deal of the artistic lift – even affixed by the camera’s eye, he remains the master manipulator, presenting his own persona as though it were a figure of his own creation: Picasso the Artist. Perhaps in a bout of his scopophilia, and without a doubt turning upside down that initial (and, I will say now, rather under-performing) definition of photography presented earlier, Picasso in his portraits appears how he thinks himself; he appears the way he wants the viewer to see him.

Perhaps therein lay the psychological, always-lurking conflict between Picasso and the lover who was also his contemporary in art, Dora Maar. When Picasso melted his subject, his beloved, to the canvas or scratched her into the plate, he seized her, adhered her reality to his imagination. Dora, exceptional in her own rite, dared to look back. The result? This is best told through her manipulation of one of those photographs taken long ago at Rue d’Astorg, which seem to show Picasso plainly. She took a knife and scratched around the face in the negative, resulting in an unkempt black halo that cancels the background and the humanizing factors of the hair, the neck, the ears. One eye – as dark and fixated as the Minotaur’s – remains.