When asked, years later, about the beginning of her affair with Picasso, Marie-Thérèse Walter said, “My mother had had a great romance with a painter. It seemed as if the same story were about to begin all over again.”* Beginning that story last week, we left off pondering how long Picasso could maintain the secrecy of this youthful love affair from his wife, Olga. When the passion – and the tension of imminent revelation – resulted in unbridled, experimental art, how long did the couple have before they’d be discovered?

With regard to their concealment, from the beginning the couple played dangerously (though, perhaps, intentionally) close to fire. Marie-Thérèse’s mother was not only aware of the artist’s involvement with her teenage daughter, but played a role in facilitating their relationship. Picasso was a frequent guest to the household, and was even invited to paint in the Walter’s garden potting shed – always accompanied, of course, by his muse.**

As time went on and feelings grew, Picasso got bolder in his trysts. He’d take Marie-Thérèse on little trips – swimming and boating, as she loved to do, at the Marne; venturing out to his old haunt, the circus, or to amusement parks. Sometimes they’d be accompanied by the artist’s young son, Paulo, who might have betrayed their confidence to Olga at any moment – but who, it seems, remained loyal to his father. Picasso even smuggled Marie-Thérèse into a nearby rental during a family trip to the beach at Dinard, using the excuse of needing a room of his own in which to work in order to rendezvous.** This particular trip was cut short in a deeply symbolic way: Olga took ill, hemorrhaging what became every day, and was whisked back to Paris for treatments that would span over the next six months. She was ill – in many senses of the word – and the marriage was, in a word, strained.

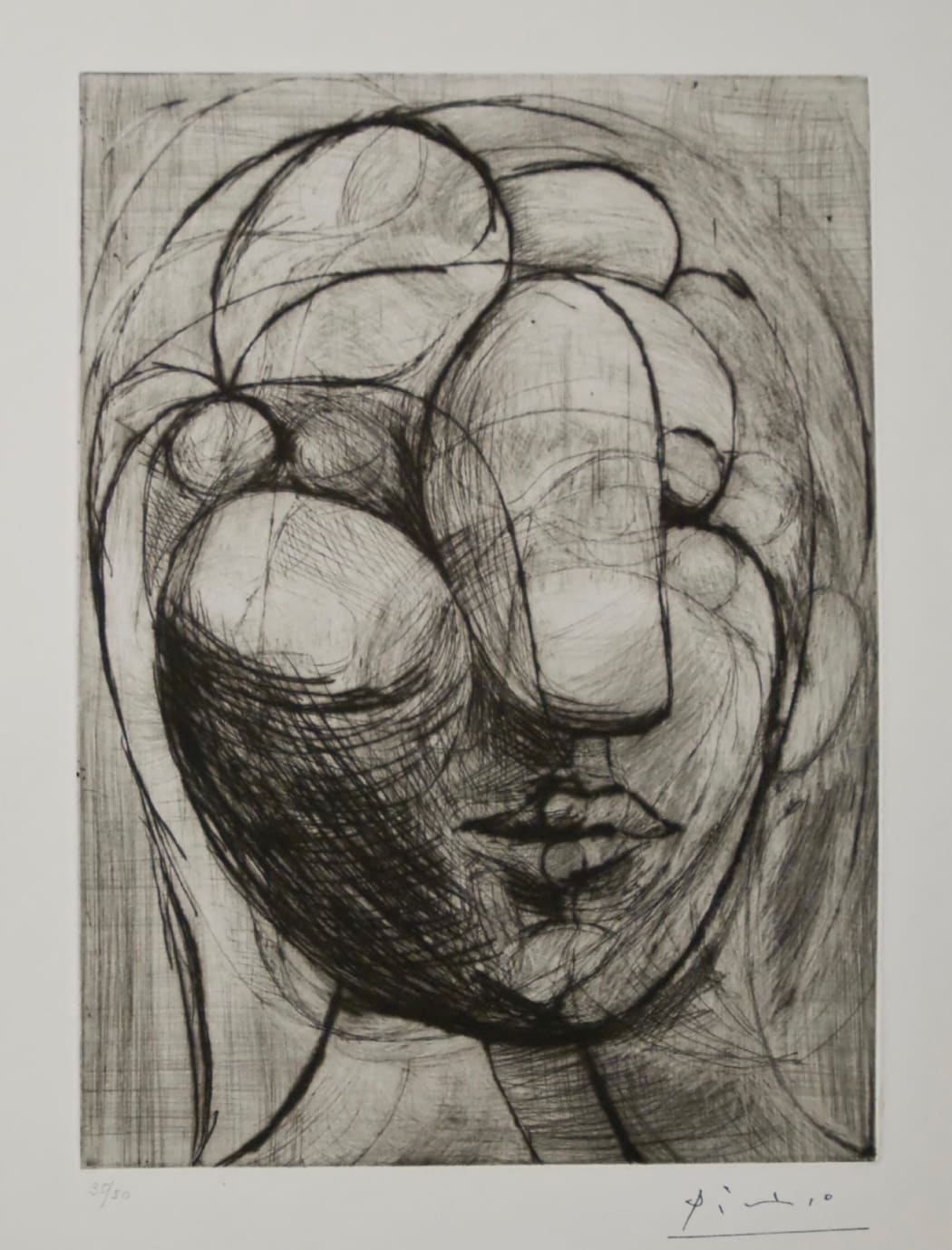

From this tense situation arose two seemingly disparate, though internally connected momentsin Picasso’s art. The first of these – his work with sculpture – was in part inspired by his desire for the elegant, classical form of his mistress. In his 1933 drypoint, Sculpture, Tête de Marie-Thérèse(B250), his model’s head appears to be in the middle of a sculptural transfiguration – her features seem at once solid, carved, fixed, as they do in rapid movement. The focal point of the piece is the beloved and unmistakable Grecian nose of Marie-Thérèse. This is mirrored in the artist’s famous sculptural work, created a few years earlier, Buste de femme (Marie-Thérèse). Here, that nose is instantly recognizable again – though this time transfigured into an engorged phallic symbol, draped upon the subject’s head.

It turns out that this same concept – the morphing of his lover’s body with his own – would spark ideas for an old project. After his friend Apollinaire’s death in 1918, he’d been asked to contribute the artwork that would adorn the monument recognizing the poet’s contributions to the Parisian creative community (you can read more about that here). When his first designs had been rejected by the conservative Committee safeguarding the monument’s planning, Picasso had dog-earred the assignment. Over ten years later, he saw a fresh way to honor his friend’s celebrated polymorphous genius, one that he felt confident Apollinaire (if not his Committee) would appreciate. The idea arose from a series of drawings he had done of Marie-Thérèse playing at the beach that summer, in which her limbs and breasts double as ballooning penises and she often carries a key, presumably striding across the sand to unlock her secret cabana. Picasso worked the clay so that this same elegant, though playfully racy, shape emerged sinuous, the distorted limbs and breasts of the subject appearing as ligaments. The resultant sculpture resembled both the morphing Bathers, and a human heart. He called it Bather (Metamorphosis I).** Though it was fittingly in memory of Apollinaire – witty, imaginative, gritty and modern – the Committee did not find it appropriate (no surprises there). The plan was rejected, but Picasso was not. He’d continue to work this same concept – hollowing it out, building it up, abstracting it – for the next thirty years.

The second emergence mentioned is more dark, and much shorter-lived – the echo, we might surmise, of the other, more bothered woman who remained fixedly in his life: Madame Picasso. With Picasso’s uptick in work – not to mention his literal materialization of his new muse – Olga was catching on. As we will discuss next week, her illness and her unhappiness would hang heavily over Picasso’s artistic psyche.