The opening line of Homer’s Odyssey goes, “Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story of that man skilled in all ways of contending, the wanderer, harried for years on end.” Kudos to Homer for his best-seller, but it sounds to me like the Muse might have had the harder job.

In ancient Greek mythology, the nine muses were goddesses who invoked artistic inspiration – our ancestral poets, painters, and musicians alike were impotent without them. But what does a modern muse look like – is she still a goddess?

We’ve talked a good deal here about Picasso’s various muses, but when it comes to Munch, the way he represented women in his art was bound up with the representation of feelings, the soul; and of course, it was coupled with the traumatic childhood memories he had of his dying mother and sister. Women: loving, but vampiric. Seductive, but entrapping. Munch’s complicated relationship with women meant complicated muses.

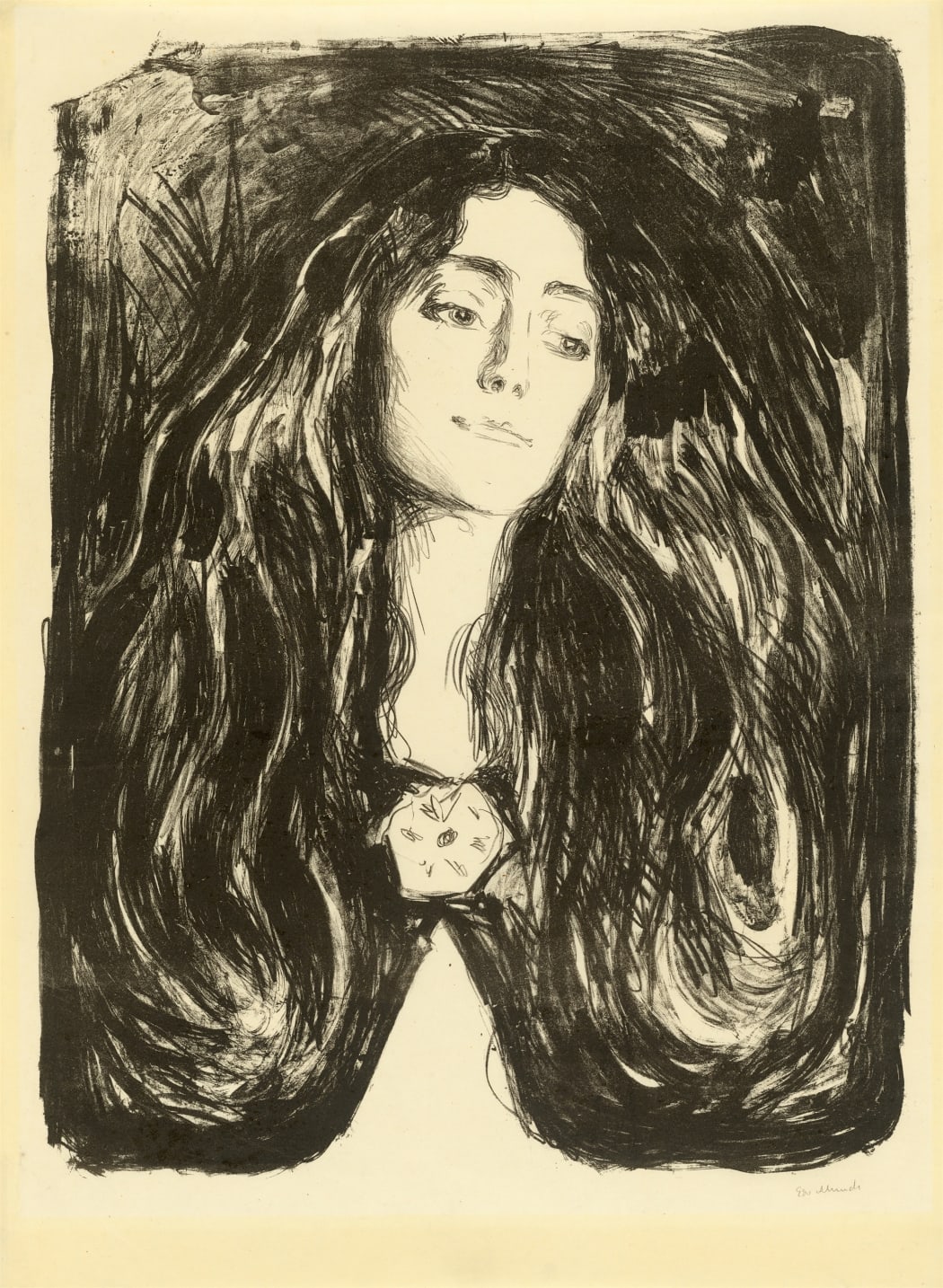

The print we explore today, The Brooch (W244), is a 1903 portrait of the violinist Eva Mudocci. Compared to some of his other images inspired by women (Life and Death (W194), The Day After (W10), or perhaps his most well-known, his Madonna(W39)), The Brooch seems like a much more quintessential example of art inspired by a beautiful muse. In the lithograph, Eva is cast radiantly with dark flowing hair. Her face is lit, her eyes big and downcast. A prominent brooch is featured in the center of her chest. Looking at the portrait with no other context, you could easily align Eva more closely with Greek mythology’s concept of the muse. However, Eva was not simply a goddess figure. She was a talented musician. An artist herself. And The Brooch wasn’t just an inspired one-off; rather, as was typical of Munch, he developed a more complex relationship with this motif and this subject. W244 is one of a small group of prints in which she is the subject.**

A bit of background: Munch had met Eva in Paris earlier that year while she was on a concert tour of Europe with her accompanist pianist, Bella Edwards. Munch was taken with her musical abilities and her beauty, and the two began an on-and-off relationship which lasted until around 1908. Though he was busy with travel plans for much of the year after their initial meeting, he maintained correspondence with Eva. He wrote to her that he’d like to do her portrait.

Though many of Munch’s lithographs created after 1902 were drawn on paper, The Brooch was executed directly on stone using a variety of techniques such as lithographic crayon, tusche, and scraping tools.**** Along with the printed lithograph of her portrait, he sent Eva a note that read, “Here is the stone that has fallen from my heart.” The motif is strongly connected to Munch’s famous Madonna composition of the 1890s. He even referred to it as “Madonna” and “Madonna with Brooch” at times. A noticeable difference however, is that the provocative elements of sexuality and eroticism present in the original Madonna are toned down in the portrait of Eva. Instead, there is more attention to the physical features of her face. The details of her lips. The way she gazes off in the distance, almost aloofly. Perhaps Munch’s personal connection to Eva played a role in his decision to highlight these features of her, as compared to the dreamlike figure of his early Madonna.

After he sent Eva her letter, Munch wrote another one to composer Frederick Delius: "But I always have feelings about the enemy – Woman I think you know Eva Mudocci and her friend B. Edvards – they are here – Fraulein Mudocci is wonderfully beautiful and I almost fear falling in love – (one of thousands). What do you think?”

Munch had a turbulent relationship with women-- an amalgam of infatuation, love, fear, and anxiety. His letter to Delius gives us a succinct glimpse into that fear; he uses the word “enemy” and the act of falling in love is makes him nervous.

And so, in the same vein as his previous muses, Munch’s relationship with Eva was doomed; a self-fulfilling prophecy, perhaps. In a third lithograph, Salome(W245), created soon after The Brooch, Eva Mudocci puts on the brooch again. She has the same flowing hair but now it’s wrapped around and encompassing Munch’s own severed head. If Munch meant us to see her as a Greek goddess, as his Muse, she’s now become Medusa.

The concept of ‘invoking the muse’ possibly suggests that a muse’s purpose is to give the artist a subject to represent. Going back to the opening line of the Odyssey, the poet is calling on the muse for help in telling Odysseus’s story. When it comes to Munch, it’s clear that his muses are a big part of his own story. However, given the profoundness of his personal struggles and emotions, as well as his ill-fated relationships, it seems impossible that he’d allow a muse to inspire his work without very literally inserting both the muse and himself into it.

I’ll leave it here for now, and look forward to discussing some of Munch’s other muses in the future. For now, wishing you joy and inspiration… in whichever way it comes to you.