-

Others have seen what is and asked why. I have seen what could be and asked why not.

-Pablo Picasso

-

-

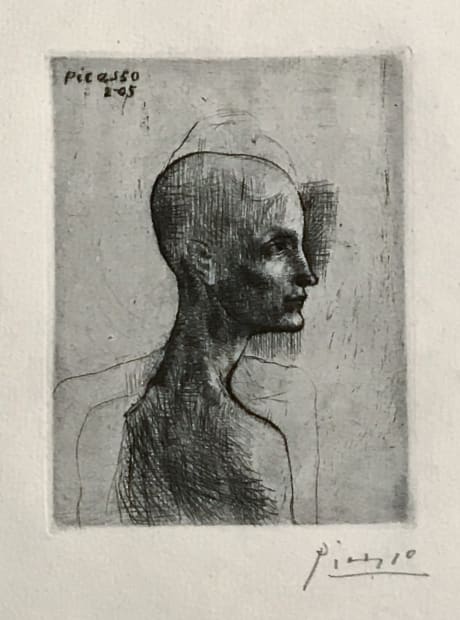

The Suite des Saltimbanques, a series of fifteen loosely-related etchings and drypoints created from late 1904 through 1905, was Picasso’s first major body of work in printmaking and is integrally connected to his paintings and drawings of the same period. These are the very first plates created by Picasso. His work from this phase is distinguished by an astonishing economy and elegance of line that reveal the artist’s immensely sophisticated eye even at this early stage in his career.

After creating the plates for the Suite des Saltimbanques, Picasso took them to the renowned printer Delâtre and commissioned a small edition of unknown size, some of which were shown in an exhibition in early 1905. Though he had gained some recognition at this point, Picasso was still quite poor and hoped to generate income from the prints. His dealer at the time, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler managed to sell some; however, most did not sell and were ultimately gifted to friends and supporters (most of these are signed and dedicated). In 1911, after Picasso had begun to achieve some renown for his Cubist work, the powerful dealer Ambroise Vollard purchased the plates. They were steelfaced to protect the delicate lines, printed by Louis Fort, and published in 1913 in an edition of 250 on Van Gelder Zonen paper and a deluxe edition of 27 or 29 impressions on Japon. Few of these impressions were signed, and if so, only at Picasso’s whim. While it is up for discussion as to the better printer, the earlier and much rarer impressions pulled by Delâtre are generally more appreciated by collectors. The quality of his impressions was excellent; unfortunately, Picasso did not enjoy working with Delâtre as he printed the plates as he interpreted them, while Fort, in contrast, carefully followed Picasso’s direction.

The French term saltimbanques refers to the itinerant acrobatic circus performers who had provided impromptu entertainment throughout Europe for centuries, at one point holding a special position at the French court performing commedia dell’arte. However, at the turn of the Twentieth Century they had long returned to their status as street performers, segregated from society and living from hand to mouth on the merits of their talents. When the Saltimbanques theme emerged in Picasso’s work, his life had recently improved after a long period of extreme poverty and relative isolation.

-

Beginning in 1900, he frequently traveled to Paris from his native Spain and had a modestly successful exhibition in mid-1901, but after the suicide of Casagemas, a close friend to the artist, he retreated to Barcelona for several years and created what are now categorized as his Blue period paintings. When he permanently returned to Paris in the spring of 1904, he joined a group of young avant-garde artists and poets living together in a large apartment building, the Bateau Lavoir, in the Montmartre neighborhood. They spent much of their time together in salon style and often visited the nearby Cirque Médrano, where the saltimbanques performed. He eventually came to know many of the performers and they became his primary subject matter. As Picasso’s art invariably reflected his own life, it is generally agreed that he saw many similarities between himself and his circle of friends in the Saltimbanques—independent, creative, and dignified in spite of their economic circumstances.

While the saltimbanques and commedia dell’arte characters had inspired artwork throughout the centuries—and, particularly, as stand-ins for the performative and isolated role of the artist in society—Picasso’s treatment of this subject stands apart for its depth and breadth, as well as its profoundly human and timeless quality.* Appearing as single figures or in groups, the subjects range in age from infants to the elderly and span a wide range of roles, from clown to friend to mother to King. Set in minimal landscapes or backstage with occasional props, Picasso imbued his subjects with poise and a sense of aloofness that belies their apparent interconnectedness, each one maintaining a strong presence as an individual, playing his or her part in the grand theater of life.

*For further discussion see E.A. Carmean, Jr. Picasso: The Saltimbanques. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1980.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Back to the Beginning: Suite des Saltimbanques

Past viewing_room