“[When I work] I have a feeling that Delacroix, Giotto, Tintoretto, El Greco, and the rest, as well as all the modern painters, the good and the bad, the abstract and the non-abstract, are all standing behind me watching me …”

—Pablo Picasso in Hélène Parmelin, Picasso Says. A.S. Barnes, South Brunswick [N.J.], 1969, 40.

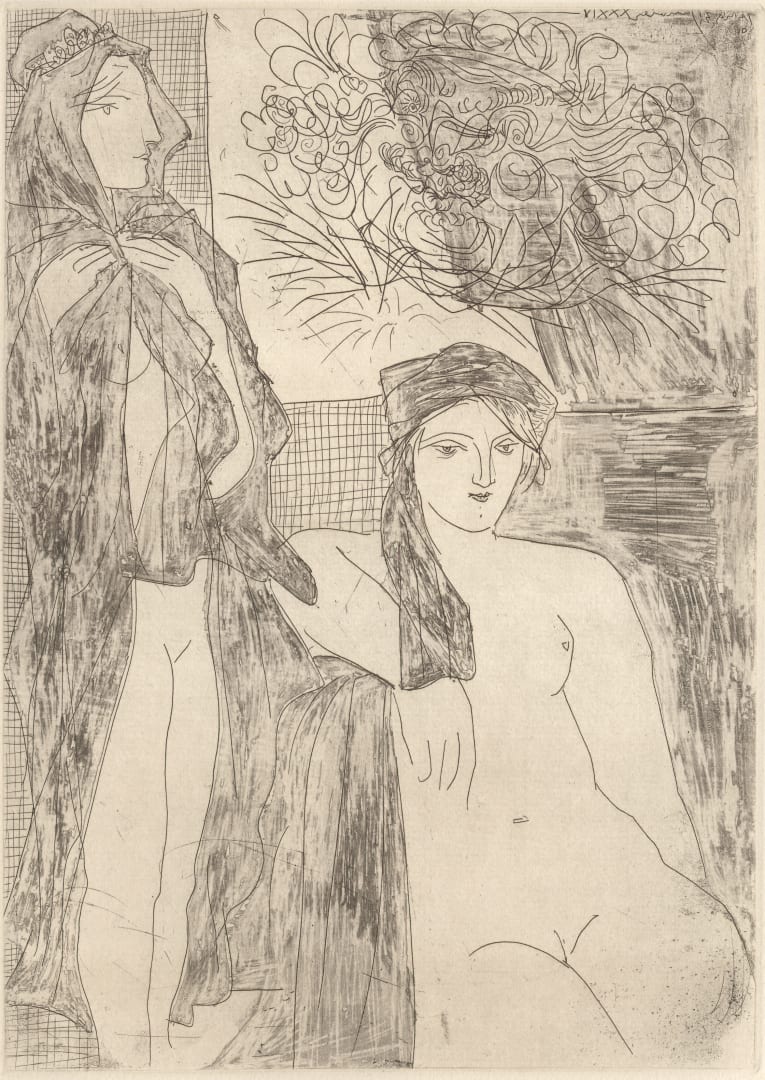

The four plates in the Suite Vollard that include images of Rembrandt, though small in number, have stimulated a great deal of speculation. Though the Dutch artist’s unkempt and wild appearance may at first seem to be out of place in this serene world of classical beauty and order, his presence is easily accounted for once it is understood to symbolize artistic genius. The Suite Vollard has frequently been interpreted as a grand allegory on the relationship between art and life, as well as the very nature of making art. Given the fact that Picasso was intensely aware of his predecessors, it seems only natural that one of them should enter into his exploration of this topic. Amongst these, Rembrandt stood out as the greatest among greats. As stated by scholar Janie Cohen, “the old master held a significant position in Picasso’s pantheon of artists and was viewed by him as a sort of artistic father figure” (“Picasso’s Dialogue with Rembrandt’s Art” in Etched on the Memory: The Presence of Rembrandt in the Prints of Goya and Picasso. V+K Pub./Inmerc.: Blaricum, The Netherlands, 2000, 80-1).

Rembrandt’s position as the undisputed master of etching was a particular source of inspiration for Picasso, and probably served as an impetus for the Spaniard to master the art of intaglio printmaking in the early 1930s. While discussing a particular plate in the Suite Vollard with his long-time dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Picasso once said, “Now I’m going … to see if I can get blacks like [Rembrandt’s]—you don’t get them at the first try” (as quoted by Hans Bolliger in Picasso’s “Vollard Suite,” Thames & Hudson, New York, 2007 [reprint of original 1956 edition], xii). In service to his goal of becoming a great etcher, Picasso developed a close relationship with the exceptionally skilled intaglio printer Roger Lacourière at this time, whose advice on technical matters had an immense impact on the artist’s development in the medium.

As explored in depth by Cohen, Picasso was intimately familiar with Rembrandt’s work in both painting and etching, and borrowed from his work on several occasions, creating his own versions of iconic themes and subjects treated by the old master. Taking this idea a step further, art historian Lisa Florman has suggested that all one hundred plates of the Suite Vollard comprise an epic elaboration on Rembrandt’s famous print The Artist and His Model, ca. 1639*—both have long been interpreted as an exploration of the Pygmalion myth in which the sculptor falls in love with his own work of art that later comes to life. If so, perhaps Rembrandt’s appearance in four plates of the Suite Vollard is Picasso’s subtle clue behind his inspiration for the etchings (Françoise Gilot with Carleton Lake, Life with Picasso, Virago Press, 1990 [reprint of 1964 McGraw-Hill edition], 177).

Whatever the reason for Rembrandt’s appearance in the Suite Vollard, it certainly generates an association with greatness in the history of art. A connection with another great era in art—the Golden Age of Greece—is also suggested in the forty-six “Sculptor’s Studio” plates in the suite. In all of these images, Picasso lays bare his ambition for his art to be held in a similar regard—a goal he was successful in achieving.

*Myth and Metamorphosis: Picasso’s Classical Prints of the 1930s. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2000, 128-39.