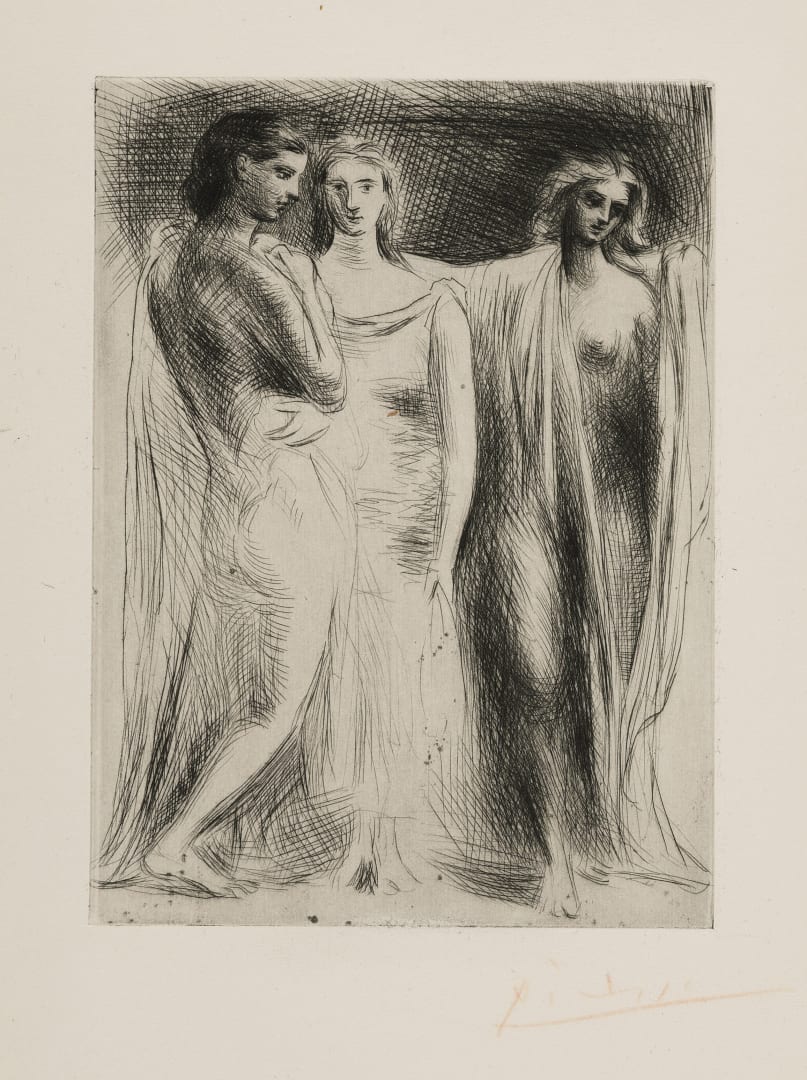

During World War I, Picasso’s focus switched from Cubism to a style influenced by classical Greek and Roman art and mythology, characterized by serene and weighty figures wearing flowing robes in timeless and minimal landscapes. This shift signaled a greater trend throughout Western Europe that would be a dominant force in art for over a decade. As always, Picasso was a leader in this new direction. In the early years of this phase, he was primarily focused on painting and drawing and created few graphic works. A majority of those he did create were for personal exploration and were not published until after the artist’s death as part of the famed Caisse à Remords.

In the mid-1920s Picasso began to make prints again in earnest upon request from two publishers: Ambroise Vollard and Albert Skira. In 1926 or 1927, Vollard invited Picasso to create illustrations for Balzac’s Le chef d’oeuvre inconnu. The Suite Vollard—arguably Picasso’s most famous suite of prints, comprised of one hundred plates—is also thought to have been commissioned around 1927. Around the same time or shortly thereafter, Picasso agreed to illustrate Ovid’s Metamorphoses for Skira. These major projects signaled the beginning of a deeper involvement with printmaking that intensified in 1934 when he began to work with Roger Lacourière, igniting a deep passion for prints that would continue throughout his lifetime.

Historians have traditionally delineated Picasso’s classical period from the years 1914-1925, at which point they agree that he moved on to surrealist-related work. Though this time span is accurate when one thinks of his unique work, Picasso remained involved with classical themes in his prints through the end of the 1930s. The reasons for this are not clear. Some have attributed it to dealer Ambroise Vollard’s influence, who preferred Picasso’s classical style to his surrealist-influenced work. However, Ovid’s Metamorphoses was commissioned by Alfred Skira, and Picasso claimed the choice of text to be his own (in Françoise Gilot’s memoire Life with Picasso, 1964, p. 191). Brigitte Baer, the print curator at the Musée Picasso and author of the catalogue raisonné of the artist’s prints, attributes it to a general disconnect between his work in printmaking and that in other media, arguing that he often used graphic media to explore alternative directions in his art. Yet another historian, Lisa Florman, has argued that Picasso’s involvement with classical subjects in his prints can be attributed to his impulse to defy convention and his belief that “there is no past or future in art. Whenever I have had something to say, I have said it in the manner in which I felt it ought to be said. Different motives inevitably require different modes of expression. This does not imply either evolution or progress, but an adaptation of an idea one wants to express and the means to express that idea” (as quoted from “Picasso Speaks,” The Arts, May 1923).*

Whatever the reasons for Picasso’s choice to develop Classical themes in his prints into the 1930s, it is important to note the stylistic differences between his canvases of the 1920s and his later linear etchings. The figures in his classical paintings have a weighty and heavily modeled presence reminiscent of sculpture and are placed in tactile, though simple, landscapes. By contrast, the figures in his classical prints are fleshy and human and exist in a dreamlike space. Some of the plates are delicately rendered in simple etched lines and others are heavily worked, employing several intaglio techniques in a single composition. Dominant themes are classical myths, artistic creation and the bullfight.

*In Myth and Metamorphosis: Picasso’s Classical Prints of the 1930s. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2000, 3-4.